آخر تحديث في: 10-01-2022 الساعة 11 مساءً بتوقيت عدن

Zurich (South24)

A prominent American research center concluded that Yemen has never been really "a unified country", and that the Unity choice by the People's Democratic Republic of Yemen and the Yemen Arab Republic in 1990 didn’t work.

This was part of a Wilson Center’s analysis by Marina Ottaway, Researcher at the Carnegie Endowment for Peace, about "War and Politics in Libya, Yemen, and Syria", which was republished by "South24".

In addition to the fact that Yemen was never truly unified, the researcher listed “other conclusions that can be reached from the history of this incredibly confusing period that have relevance to the present including that although the country was not even remotely a democracy, it had an active and pluralistic political life, with competing power centers in political parties, tribes, organizations based on sectarian identities and ambitious individuals”.

However, according to the Wilson Center, this political activity could not be contained within the framework set by formal institutions, but kept spilling over the boundaries between political and military action, and eventually caused the system to break down.

Unity and war

The analysis added that: “Yemen in its present borders is not a unified country but an unstable amalgamation of different regions, political movements, and tribal groups. The two major components are North and South Yemen”. The report claimed that “neither of which is a cohesive unit” as "North Yemen was historically controlled by an Imamate, which was overthrown in 1962 leading eventually to the formation of the Yemen Arab Republic” while “South Yemen emerged in 1970 when the British relinquished control of the city of Aden, which they had occupied since 1839 as part of the effort to secure the maritime route to India, and of a number of self-governing protected territories to the east”.

According to the analysis “Southern Yemen, somewhat improbably, established a government with a strong socialist orientation, calling itself the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen (PDRY). Despite their divergent previous history, the Yemen Arab Republic and the PDRY opted to unify into the Republic of Yemen in 1990. Unification did not work, with the South resenting what it perceived as the domination by the North. A brief war between the two parts of the country erupted in 1994, ending with the defeat of the South and the re-imposition of unity”.

After the military win in 1994, “the Republic of Yemen gave itself the trappings of a modern republic, with an elected parliament and political parties. It held elections in 1993 and again in 1997 after the 1994 conflict. As a sign of the country’s fragility, the 1997 elections were boycotted”.

The analysis added: “This façade of a democratic process led Yemen to be chosen in 1999 to host a conference of small democracies, funded by the US State Department and organized by the National Democratic Institute. In reality, there was no democracy in Yemen in 1999, as conference participants saw firsthand, being shuttled around town in heavily armed convoys travelling on closed streets. The country was essentially run by President Ali Abdullah Saleh with the support of the military, the General People’s Congress (GPC), and intermittently of Islah, an Islamic Party that also had the support of some tribes”.

She continued: “In 2003, Yemen managed to hold a third and last parliamentary election after a two-year delay. More than twenty parties participated, most winning no seats. Saleh’s GPC won the overwhelming majority of seats, causing other parties to coordinate their efforts”.

Beginning in 2005, Islah joined the YSP and other smaller organizations in what came to be known as the “Joint Meeting Parties” defeating Saleh’s attempt to keep Islah on his side and pit it against the YSP.

After 2011

The analysis discussed the “The unstable situation in Yemen worsened in 2011, when students took to the streets in Sanaa. It was an uprising similar to those many other countries were experiencing at that time, but it shook the country’s unstable balance to the core”.

It said that “The emergence of the Houthis and the Southern separatist movement created an insurmountable problem. Between November 2011, when Salah agreed to the GCC transition plan and the holding of the National Dialogue conference, both had grown in power and importance. Both were represented at the National Dialogue Conference, indeed each had a member on the 9-member presidency of the dialogue, but in the end they did not see the dialogue as a solution to their problems or an answer to their aspirations”.

According to the analysis, “the Houthi movement had started in the 1990s to represent the grievances by the Zaydi Houthi clan in the northern Saada governorate and their rise greatly alarmed Yemen’s Sunni neighbors, who saw the long hand of Iran behind the Houthi movement”.

The analysis believes that “the Iranian involvement, probably limited at the start, grew as the movement became more successful. A local rebellion thus became part of the regional Sunni-Shia conflict and of the conflict between Iran and the Sunni Gulf monarchies. The United States kept its direct involvement minimal, but its sympathies were and remain with the Sunni forces and against any Iranian-backed entity”.

By the time of the National Dialogue Conference, “the Houthi movement had spread to a large part of the north and was on the verge of occupying the capital Sanaa — it did so in late 2014. The movement had grown too powerful to accept the offer of control over two land-locked provinces in the center of the country, which the Conference offered them as part of the federal solution”.

The researcher claimed that “One of the factors behind the Houthis’ success was their alliance with former President Ali Abdullah Saleh, who was down but not out and still had troops that remained loyal to him. The alliance with Saleh eventually broke down and Saleh was killed in 2017, but Houthi power was by then well established and kept growing. The occupation of Sanaa by the Houthis forced President Hadi into exile in Saudi Arabia, from where it made sporadic forays into Aden, the official interim capital. It also caused Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates to intervene in the conflict.”

Federation and separation

Meanwhile, “separatist tendencies in the South rapidly reemerged. Discontent in the South continued to fester after the 1994 war and by 2007 the area was rife with political movements held together loosely by the grievances against the North“according to the Wilson Center.

“The federal solution offered by the National Dialogue Conference did not pacify the southerners any more than it had pacified the Houthis. Southern movements had become too well-established and determined in their separatist ambitions. They had also gained outside support, particularly on the part of the United Arab Emirates that had come to see the separation of the south as a better alternative to the continuing strife.” the report said.

It went on by saying that “The federal solution offered by the National Dialogue Conference did not pacify the southerners any more than it had pacified the Houthis. Southern movements had become too well-established and determined in their separatist ambitions. They had also gained outside support, particularly on the part of the United Arab Emirates that had come to see the separation of the south as a better alternative to the continuing strife”.

Although, “the many southern movements never unified, the Southern Transitional Council (STC) emerged after 2017 as the most influential. By 2021 it controlled much of the southern provinces, leaving the official, internationally recognized government of President Hadi, already besieged by the Houthis, without much of a country to rule”.

The failure of the National Dialogue Conference

The analysis concluded that “the National Dialogue Conference in the end failed to steer Yemen toward a political solution, but a military solution through the triumph of one group also remained impossible. Instead, Yemen remains bogged down in the power plays of groups increasingly inclined to rely on force”.

Instead, the analysis indicated that “the Houthis continue to fight to expand the area they control, and civilians pay the price in starvation and disease. Hadi, nominally still president, does not govern the country. Saudi Arabia continues to support him in the hope of preventing the power of the Houthis and their Iranian backers from increasing further, and for lack of a better alternative”.

The UAE, according to the researcher, “sees the separatists in the south as part of the solution to the intractable Yemen problem” while “the United States does not want to fight the Houthis, but remains involved in Yemen because it worries about the presence of al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula in parts of the South and about Iran’s backing of the Houthis”.

The analysis concluded that “after a decade of turmoil and war, no solution is in sight”.

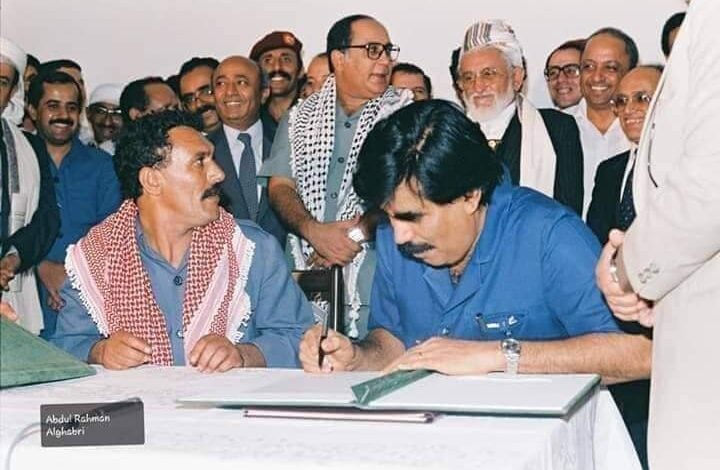

Photo: South Yemen and North Yemen state presidents sign the Yemeni Unity Agreement May 22, 1990 (archive)