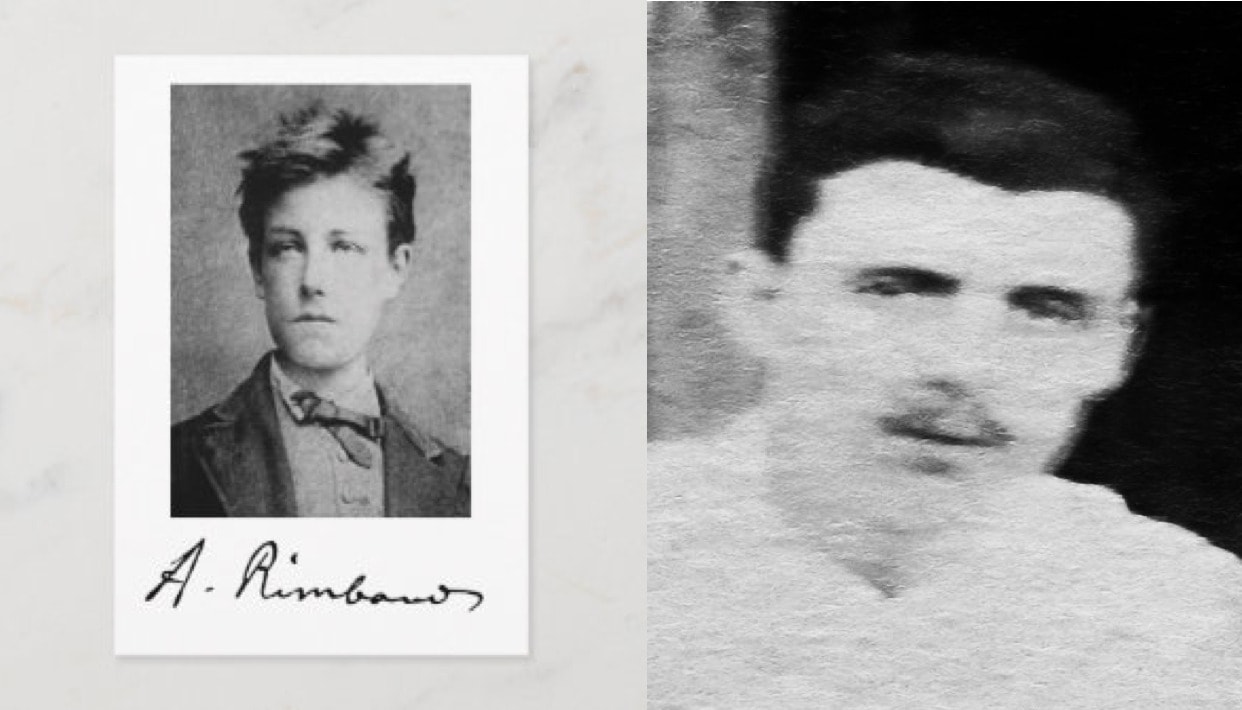

Photo: Jean Nicolas Arthur Rimbaud (archive)

آخر تحديث في: 01-05-2023 الساعة 11 صباحاً بتوقيت عدن

Fatimah Johnson (South24)

The great city of Aden was once home to the most glamorous coffee foreman who ever took up such a post. Jean Nicolas Arthur Rimbaud, was a sparkling brilliant figure – he was a rebel [1]. He was a poet born, born in Charleville, France 1854. His life in France has led to him being regarded as a cultural icon, held in the highest respect that he deserves. Political nonconformist and poet, the late Saadi Youssef of Iraq, wrote in 1981 that both Arab and French poets as well as intellectuals, ought to carry roses and wine to Aden as offerings to be put at the feet of a statue of Rimbaud as part of yearly pilgrimages to honor the craftsman [2].

Five humble coffee beans were found during the restoration of the house in Aden in which Rimbaud used to live. In anthropological terms, these coffee beans are artifacts that reveal volumes about Aden’s culture and development by 1880 (the year Rimbaud arrived in Eudaemon Arabia – Aden’s classical name). A wall in the House of Poetry, as Rimbaud’s House is also known, was beautified with five decorative cavities all bearing the French word for coffee, café. The beans were curated and a photograph of them was used in an exposition entitled “Aden: Rimbaud’s House Exhibition” [3].

Cosmopolitan Aden was home to the French Bardey & Co export agency that took Rimbaud on as an employee [4]. Pierre and Alfred Bardey were entrepreneurs from Lyon who capitalized on the massive popularity of coffee in France as well as the high quality of North Yemen’s coffee cherries. In 1880 about half of the North Yemeni coffee crop was shipped to Marseilles via South Yemen’s Aden [5]. Such a feat was made all the more possible by the 1869 opening of the Suez Canal.

The Port of Mokha in North Yemen once dominated the world trade of coffee for some 200 years [6]. This dominance was facilitated by South Yemen’s importing of coffee beans from North Yemen and the re-exporting of them via Aden, home to the deepest port in the world, a major and busy commercial centre for maritime trade, passenger ships as well as ship-bunkering (re-fuelling) and duty free goods in the 19th century [7]. Prior to re-export from Aden, the coffee beans had to be selected. This was Rimbaud’s occupation in Aden. He supervised the selection as overseer for a group of female Hindu workers [8]. This would have taken place at what is known as “Rimbaud’s House” but in truth this was a rented premises by Bardey & Co from the distinguished Yemeni Jewish Menachem Messa family in Aden [9] and served as a vast coffee sorting office, though he is known to have also lived there. The process of sorting coffee is a highly specialized and difficult one. This had to be done manually or through the use of sieves in the 19th century. This process is crucial so that the beans can be classified in regards to size and shape amongst other factors. In addition, coffee beans are often roasted and tasted at this stage to determine how they will be classified in terms of quality which relates to the market price [10]. We see in this story of the coffee trade, evidence of Aden’s economic sophistication and ethnic hybridity.

It is to be noted that most biographies of Rimbaud describe his life after he left France for the wider world as a stage where he had completely abandoned art, even describing him as an “energetic capitalist” [11]. However, there is something deeply artistic about coffee in the sense that coffee itself goes on a journey. Coffee before it is really coffee, transforms from green cherry to red cherry to dark brown seed after the fruit is removed – it seems it is a fruit and seed after any artist’s heart. The hard seed, that is the coffee beans, had to be closely examined and even sampled on the palate by Rimbaud before he allowed them to be released to the coffee shops of Europe. Coffee (Coffea arabica) itself has a deeper journey – originating in an evolutionary sense in North Yemen via a mating process some 20,000 years ago of two different parent species of wild Ethiopian coffee, coffea canphora and coffea eugenioides [12]. Such a beautiful history and sorting process appears to require the talents of a thoughtful, sensitive person and hardly seems the work of energetic capitalism. Let us also not forget that coffee is actually a hard drug [13] - helping people to take it seems like apt work for the rebel poet.

The rebel poet had not been a rebel poet though for some five years before he came to Aden. Rimbaud ended all written artistic expression by 1875. This is one of the most striking features of his life in South Yemen, he had denounced his own work to Alfred Bardey as “absurd” and “disgusting” [14]. His transformation from artist to coffee foreman is seemingly unexplainable. Biographers of Rimbaud have looked for clues in his work that might indicate his eventual decision to choose life without art and it is hard to not imagine that the key to his mysterious presence in Aden lies in his writing. For example in Illuminations, a set of prose poems written between 1873-1875, Rimbaud writes: “Je suis maître du silence” (I am master of silence) [15]. In the section called Adieu (Farewell) in Une Saison en enfer (A Season in Hell), a prose poem from 1872, he writes: “J'ai vu l'enfer des femmes là-bas; - et il me sera loisible de posséder la vérité dans une âme et un corps”. (I experienced a hell women know well—and now I’ll be able to possess truth in a single body and soul) [16]. Consider also the charming poem by Rimbaud called Roman (Romance) where he writes: “On n'est pas sérieux, quand on a dix-sept ans” (When you are seventeen you aren’t really serious) [17]. When Rimbaud moved to Aden he was twenty-five. The second picture at the beginning of this article was taken as Rimbaud sat on a veranda at the Hôtel de l'Univers (Universe Hotel) in Aden, August 1880 [18]. The image contrasts starkly with that of the first picture above, where Rimbaud looks every inch a wild tortured teenager complete with burning dark eyes and jagged rough hair. In the second image he looks decidedly mature and even conservative. His hair is neatly cut back while he wears a small moustache and a clinical white shirt. True to his poem Roman, Rimbaud was not serious when he was seventeen and when he was twenty-five in Aden he simply was.

At one point in South Yemen’s history, Rimbaud’s House was renovated to accommodate the French Consulate, a research centre, a cultural centre and a library. Starting in 1991, annual conferences on poetry were also held at Rimbaud’s House [19]. The respect and admiration for Rimbaud emerges from his posthumously acquired reputation of being one of the first modern poets. Rimbaud’s poetry and his thinking (revealed in letters he wrote) is known for its intense efforts at introspection and self-awareness. He once penned these brilliant words in 1871: “Je est un autre” (I is someone else) [20]. He dared to talk against self-interest and lambasted France’s colonial projects when he wrote in Mauvais Sang (Bad Blood): “Les blancs débarquent. Le canon! Il faut se soumettre au baptême, s'habiller, travailler” (The white men are landing. Cannons! Now we must be baptised, get dressed, and go to work) [21]. Rimbaud also rejected the poetic conventions of his era and went further by mocking them. For example, he refused to write in praise of the Roman goddess of love, Venus, and instead wrote a poem in which she is described as having an ulcer on her anus (in Vénus Anadyomène). He did even more than mock, which takes great courage and leads to progress, he also played around with poetic form. In his delightful poem Voyelles (Vowels), all five vowels are given a fixed color. A is black, E is white, I is red, U is green and O is blue. The vowels become like labels for the brain to attach itself to when the poem is heard. Hearing Voyelles, a person “hears” in color as each vowel punctures the verses [22]:

Golfes d'ombre; E, candeur des vapeurs et des tentes,

Lances des glaciers fiers, rois blancs, frissons d'ombelles;

I, pourpres, sang craché, rire des lèvres belles

Dans la colère ou les ivresses pénitentes;

(Gulfs of shadow; E, whiteness of vapours and of tents,

Lances of proud glaciers, white kings, shivers of cow-parsley;

I, purples, spat blood, smile of beautiful lips

In anger or in the raptures of penitence).

Ten years after Rimbaud had been shot with a Lefaucheux revolver in Belgium by his lover, French poet Paul Verlaine, (the gun was sold for $460,000 at auction) [23] he told his family in an 1883 letter that he was beginning to “lose the taste for… living and even the language of Europe” [24]. He is known to have acquired fluency of Arabic whilst in Aden, he gave lessons on the Qur’an, he bought a camera and intended to write a book on Harer. He moved between Aden and Harer for eleven years (1880 to 1891). Before arriving in Aden he had been in Germany, Italy, Austria, Belgium, Indonesia, Denmark, Norway, Egypt and Cyprus. Between living in Aden and moving back and forth from there to Ethiopia, he sold rifles to Sahle Miriam [25] who eventually became the Emperor of Ethiopia (Menelik II) and who completed a historic defeat of an Italian invading army in 1896. Rimbaud took another lover in Aden, an Ethiopian woman who lived with him for two years. Enviable frantic activity is what he practised, “free freedom” [26] as he described it.

“The central government is destroying Aden’s architecture and history because it was the capital of Yemen’s South Republic. They are killing the spirit of the city” [27]. This is the view of Muhammad Al Saqqaf, Chair of the Aden Heritage Foundation who spoke to the Al Jazeera news agency about the woeful neglect of Rimbaud’s House and other important historical sites in Aden. Sadly, Rimbaud’s House is no longer used for diplomatic, cultural and educational purposes. As of 2014, its ownership passed to a businessperson and consumer goods (furniture) are being sold from the two-story building. The diminished importance attached to Rimbaud’s House, which appears to be politically driven, decreases the sense that South has a unique history to North Yemen and weakens the case for independence from the North. Rimbaud is part of South Yemen’s historical fabric – this is what his life in Aden illustrates - thus he is also bound up in her contemporary history. Congruent to this is the vital need to understand that Rimbaud’s House must be preserved and preserved in a way that reflects his role in the South’s history: “Aden is my identity and my history, if I cannot preserve it I’ll lose my past and my future” [28].

Journalist

Photo: Jean Nicolas Arthur Rimbaud (archive)

[1] newyorker.com

[2] Taminian, Lucine. Rimbaud’s House in Aden, Yemen: Giving Voice(s) to the Silent Poet. Cultural Anthropology, vol. 13, no. 4, [Wiley, American Anthropological Association], 1998, p.464 jstor.org

[3] Taminian, Lucine. Rimbaud’s House in Aden, Yemen: Giving Voice(s) to the Silent Poet. Cultural Anthropology, vol. 13, no. 4, [Wiley, American Anthropological Association], 1998, p.464 jstor.org

[4] mag4.net

[5] peterpickering.wixsite.com

[8] Taminian, Lucine. Rimbaud’s House in Aden, Yemen: Giving Voice(s) to the Silent Poet. Cultural Anthropology, vol. 13, no. 4, [Wiley, American Anthropological Association], 1998, p.464 jstor.org

[9] peterpickering.wixsite.com

[10] attibassi.it

[11] newyorker.com

[13] mcgill.ca

[14] newyorker.com

[15] mag4.net

[16] my-blackout.com

[17] mag4.net

[18] newyorker.com

[19] Taminian, Lucine. Rimbaud’s House in Aden, Yemen: Giving Voice(s) to the Silent Poet. Cultural Anthropology, vol. 13, no. 4, [Wiley, American Anthropological Association], 1998, p.464 jstor.org

[20] newyorker.com

[21] mag4.net

[22] mag4.net

[23] bbc.co.uk

[24] mag4.net

[25] nytimes.com

[26] newyorker.com

[27] aljazeera.com

[28] aljazeera.com