Archive

آخر تحديث في: 01-05-2023 الساعة 11 صباحاً بتوقيت عدن

Fatimah Johnson (South24)

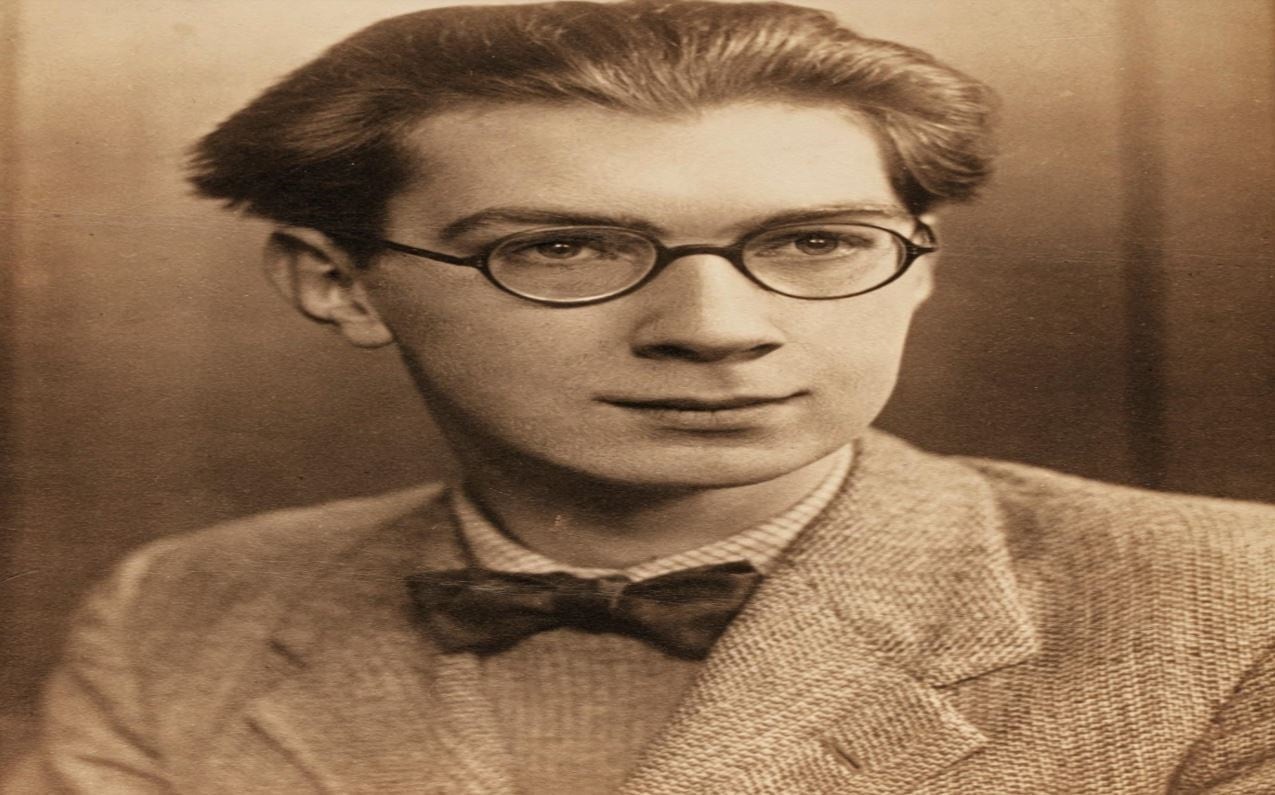

Coventry born, the enigmatic Philip Larkin (1922 – 1985), wrote a short but elegant poem about Aden. He is regarded by British people and those beyond as one of the greatest poets of that nationality. The heavyweight British newspaper, The Times which was established in 1785, voted him to be the best post World War II poet [1]. His memorial stone in the medieval Westminster Abbey (especially made of Purbeck stone sourced from the Jurassic Coast, a 95 mile landscape that stretches from Devon to Dorset and a UNESCO World Heritage site [2]) lies with other literary stars like Lewis Carroll and D.H. Lawrence. The poem is called Homage to a Government. It first appeared in the sister newspaper to The Times, The Sunday Times, on 19 January 1969 [3] and then in his collection called High Windows in 1974.

The poem is a lyric of half rhyme repeating words that create the effect of profound disillusionment as each word worms itself into your mind: Next year we shall be easier in our minds [4] and the druggy rhyming pattern of ABCCAB make each stanza like junky fractures. In this sense it is similar to the Poem in Four Cantos in Vladimir Nabokov’s Pale Fire which also features in the film Blade Runner 2049 where the words within cells interlinked are used to stultify the reader/listener.

Fury is the first thing you sense when reading Homage to a Government. The poem starts with an anonymous year (Next year) and Aden is never named in the poem itself, but no-one at the time of publication could have doubted the subject matter was in fact Aden. The death of British rule in South Yemen after approximately 130 years was a source of great trauma for Britain. Aden was described in June 1967 in the British Parliament as “one of the last two great imperial commitments” [5] of Britain (the other was Hong Kong). In the same sitting of the British Parliament, a Labour member made extraordinary admissions about Britain. Christopher Mayhew, described Britain as not having real power, that it was capable only of paper peace keeping and as having a pretentious as well as a contradictory policy towards the Middle East. The candid and pragmatic view of Mayhew on Aden and the Middle East in general is not shared by Larkin. The opening of Homage to a Government is sarcastic, angry and critical: Next year we are to bring the soldiers home / For lack of money, and it is all right. Larkin is quoted as saying: “… to bring them [troops] home simply because we couldn’t afford to keep them there seemed a dreadful humiliation” [6]. Put into context, Britain had moved from being one of the world’s superpowers since the mid-1850s to being reduced to shameful penury – too poor to fulfill meaningful responsibilities in the world. The British philosopher and winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature, Bertrand Russell (born in 1872), in an interview from 1952 explained that English people regarded English naval supremacy as a sort of law of nature, that Britain literally ruled the waves of all the seas and that they never believed that this would end.

A reference to the attack on Aden on 3 July 1967 led by Lt Colonel Colin Mitchell (Mad Mitch) to quell rising South Yemeni nationalism is sequenced in Homage to a Government. But the reference is Delphic – Larkin refuses to either condemn or condone Mitchell’s actions in Aden: and from what we hear / The soldiers there only made trouble happen.

Larkin’s take on South Yemeni nationalism in the poem is a somewhat ill-informed one. The poem reveals that, to a point, he does recognize Aden’s high economic and political value and the threat to her from opportunists, hostile neighbor states in the present as well as the past imperial powers outside of Britain (the Ottomans and the Portuguese). South Yemen’s value was more properly stated by the late Frank Hooley, a Labour Party British politician in 1967:

the corner of the world [South Arabia] that we are now discussing is of immense importance to every country. The mere fact that it has been held for so long as a large and important military base demonstrates its strategic importance and indicates how vital it is in the concept of power relationships between countries in the area and throughout the world. The world community has shown an interest in its future in the past three or four years [7].

In Homage to a Government, Larkin does not go one step further and acknowledge the powerful reality of Arab nationalism in its South Yemeni form. Instead, he reduces Aden to: Places they guarded, or kept orderly, / Must guard themselves, and keep themselves orderly. This section of the poem denies the darker side to the colonial era – Britain’s self-serving reasons for being in Aden at all, the brutal methods used by British regiments particularly in 1967 and Britain’s tactic of keeping areas outside of Aden in South Yemen underdeveloped. Similar to Rudyard Kipling’s The White Man’s Burden The United States and the Philippine Islands (1899), Larkin posits the now distasteful view that colonial projects are civilizing, necessary and benign. What else it also denies is the role of actual South Yemenis in bringing about this massive change – launching an independence movement, deciding the point at which Britain would quit, their successful use of arms and their ability to administer a new state, the People’s Republic of South Yemen [8]. Once again, Larkin is in disagreement with the political leaders of the time. In June 1967 British Foreign Secretary George Brown said:

I therefore stand on what I have said. If F.L.O.S.Y. or the N.L.F. representatives are ready to talk, the Federal Government are ready to talk with them. We certainly are [9].

Homage to a Government marked a major shift in Larkin’s method as a poet. Prior to the late 1960s, Larkin claimed that he had “never been didactic, never tried to make poetry do things” [10]. However, in Homage to a Government, he directly attacked Harold Wilson who headed the British Government at the time on a highly topical issue (the British presence in Aden) and took a right-wing stance. It was the first time he had placed his poetry into the political arena and made obvious his political prejudices. The decision to quit Aden is presented as perfidy [11], the voice of the poem is intended as an ordinary British Citizen who is attempting to justify his elected but corrupt government amidst interjections from a voice that is obviously Larkin’s own: We want the money for ourselves at home / Instead of working. And this is all right.

Despite adding one highly political poem to his oeuvre, Larkin did not have a sophisticated, clearly defined political outlook [12]. In fact, he later tried to deny to one interviewer that Homage to a Government was about politics and claimed it was “really history” [13] in the sense of being about something firmly in the past. What he was clear on though, was his right-wing extremism if not the reasons for it:

I’ve always been right-wing. It’s difficult to say why, but not being a political thinker I suppose I identify the Right with certain virtues and the Left with certain vices. All very unfair no doubt [14].

It may be that the combination of his right-wing attitudes and his commitment to public poetry [15] (reflecting on contemporary issues that affected British people) incited him to write Homage to a Government even if he himself was politically superficial. He told Monica Jones, his partner, in 1953 (long before Harold Macmillan’s Wind of Change speech [16] in 1960 in South Africa in which Macmillan vented his fears that people in Asia including South Yemen would eventually fall into the “Communist camp”) that:

You know I don’t care at all for politics, intelligently. I found that at school when we argued all we did was repeat the stuff we had, respectively, learnt from the Worker, the Herald, Peace News, the Right Book Club (that was me, incidentally: I knew these dictators, Marching Spain, I can remember them now) and as they all contradicted each other all we did was get annoyed. I came to the conclusion that an enormous amount of research was needed to form an opinion on anything, & therefore I abandoned politics altogether as a topic of conversation [17].

Homage to a Government is only three stanzas but as we have seen, it is busy for all that. Each graceful stanza is a sexain (made up of six lines). In these sexains, Larkin delicately places lampooning barbs as he criticises the British Government of 1967 and its people for effectively dismantling what countries the British Empire still held as imperial possessions for what he perceived as thoroughly dishonorable reasons: Next year we shall be living in a country / That brought its soldiers home for lack of money.

The word money is used disapprovingly four times as though Larkin is unaware of the grave economic problems Britain was facing (the attempt to keep pound sterling stable at a value that had been fixed in 1949 [18]) from the mid 1960s onwards and that these in part forced Britain to transfer power over to South Yemeni nationals. Larkin’s distaste for the British Labour Party’s policies is clear from the poem: money saving policies that would allow for greater public expenditure in Britain itself, appeasement of Trade Unions who were seeking higher wages for union members, maintaining financial grants to those British people unable to find employment. The ideological situations in Britain and South Yemen at the time provoked his right-wing sensibilities, enough for him to say in the poem that leaving Aden would transform Britain for the worse, into a different country, into a state of inchastity whose identity is only based on money.

Homage to a Government is a remarkable achievement, a poem that acts as a historical tour de force. It immortalizes eternal Aden in culture because as Larkin said in an interview: “When you’ve read a poem, that’s it, it’s all quite clear what it means” [19].

[1] thetimes.co.uk

[3] Philip Larkin – Life, Art and Love, James Booth, Bloomsbury, New York, 2014, p288

[4] Philip Larkin – Life, Art and Love, James Booth, Bloomsbury, New York, 2014, p288

[6] The Poet’s Plight, James Booth, Palgrave Macmillan UK, Hampshire, 2005, p136

السابق: