South24 Center

08-02-2024 الساعة 12 مساءً بتوقيت عدن

What’s being proposed is for the STC to creatively utilize the converging Red Sea and Horn of Africa Crises for the purpose of advancing South Yemen’s interests with a focus on clinching partnerships with the BRICS countries.

Andrew Korybko (South24)

Converging Crises

The Red Sea Crisis that was provoked by the Houthis’ attacks against civilian vessels in solidarity with Hamas and the Horn of Africa one brought about by the Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) between Ethiopia and Somaliland offer unique strategic opportunities for South Yemen. The first catapulted regional security concerns to global attention while the second did the same for the cause of restoring state sovereignty. This new focus on both can work to South Yemen’s benefit.

Security Interests

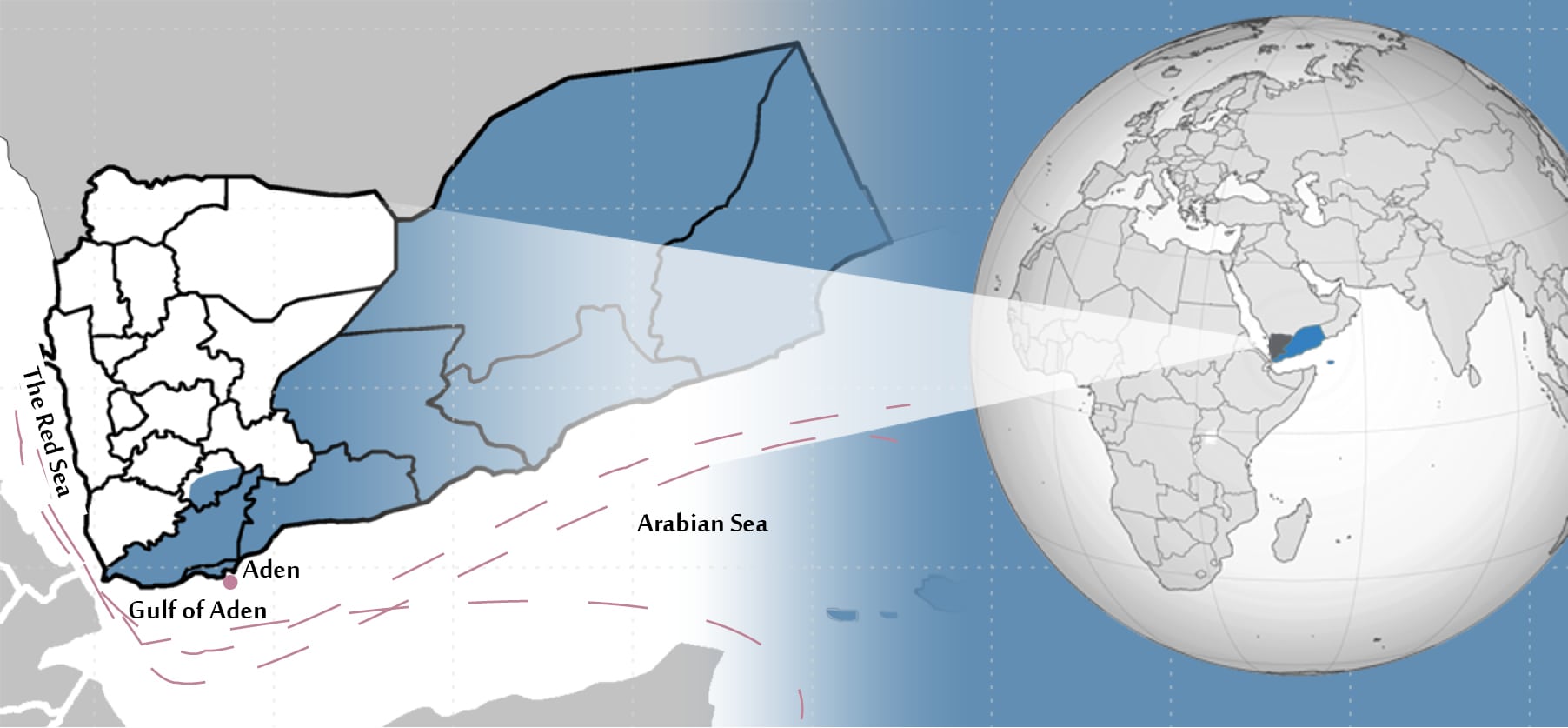

Responsible extra-regional stakeholders are looking for reliable security partners that can help them fight terrorism, combat piracy, and protect the Sea Lines Of Communication through the Gulf of Aden-Red Sea (GARS) region upon which European-Asian trade is dependent. All three goals can be advanced through bilateral agreements with South Yemen, whose representative Southern Transitional Council (STC) plays an important role in Yemen’s internationally recognized Presidential Leadership Council (PLC).

Although South Yemen hasn’t yet restored the sovereignty that it lost after agreeing to the failed unity project with North Yemen after the end of the Old Cold War, it’s gradually making progress on this in alignment with the STC’s stated mission, which reflects the will of the South Yemeni population. The STC-PLC interplay remains complicated, but the important role that the group plays in this body could possibly lead to a future confederal plan as the first step towards restoring sovereignty by referendum.

However events unfold, the point is that the STC is gaining legitimacy for its cause through its position in the PLC, which can in turn be leveraged after some time depending on the course of domestic dynamics to promote bilateral security dealings with state-level actors who have shared regional security interests. This is what the group should aspire for, namely the clinching of agreements for providing direct security support for bolstering anti-terrorist and -piracy capabilities as well as possible naval cooperation.

The model pioneered by the STC and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) can serve as the basis for other military partnerships with countries like Russia and India, who now count the UAE as a fellow member of BRICS and have similar regional security interests as it and the STC. The Sudanese Civil War complicated Moscow’s plans to open up a naval base in Port Sudan, while the recent spate of piracy has refocused India’s security attention to the GARS region, where it’s now interested in establishing a naval presence.

Both are therefore actively searching for reliable security partners that can help them fight terrorism, combat piracy, and protect the SLOC upon which their bilateral trade – which is comprised mostly of fertilizer, fuel, and military-industrial equipment, all of which are immensely strategic – depends. South Yemen is the perfect partner for them due to its advantageous location, its complementary search for foreign partners (driven by the pursuit of political recognition), and those two’s historical ties with it.

Russia’s were formed during the Old Cold War while India’s stretch back to the shared British imperial period, but each could soon renew these ties since they form the basis for building mutually beneficial partnerships in the future. Russia already has ties with the STC whereas India has yet to establish them, but it could rely on the group’s Russian and/or UAE partners – both of whom have close bilateral relations with Delhi – as a means of initially reaching out to the group.

India’s political sensitivities over Kashmir might make policymakers reluctant to formally initiate direct contact with this sovereignty-aspiring group so it’s reasonable to expect India to informally request Russia and/or the UAE to put it in touch with the STC. Those two could then probe the possibility of establishing some sort of ties based on shared regional security interests. That approach wouldn’t be unprecedented either since it was already applied last month vis-à-vis Iran and the Houthis.

Indian External Affairs Minister Dr. Subrahmanyam Jaishankar raised his country’s concerns over Houthi attacks on civilian vessels during his trip to Tehran at that time due to the Islamic Republic’s political and military ties with that group. This indirect dialogue model could easily be applied vis-a-vis Russia and/or the UAE to establish indirect contact with the STC, after which India could then decide whether to pursue this opportunity more if policymakers feel comfortable enough with it.

Diplomatic Interests

Bridging South Yemen’s security and sovereignty goals, the latter of which will round out the last part of this analysis, is the intermediary step of prioritizing relations with key BRICS countries on the basis of the previously mentioned shared regional security interests. Russia and India’s were already described while the UAE’s are well-known, but Ethiopia should be courted as well due to its newfound membership in that association and recent prioritization of its peaceful port plans via the MoU with Somaliland.

About that agreement, Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed elaborated on the reasons why his country needs to restore reliable access to the sea in a nearly hour-long address to parliament last fall, which can be watched here with English subtitles. In brief, it boils down to preemptively averting domestic and international crises stemming from Ethiopia’s reliance on SLOC for economic stability, particularly the import of fertilizer and fuel. These can only be confidently protected by rebuilding the Ethiopian Navy.

He recently defended the MoU with Somaliland in parliament as being driven by mutual economic and strategic interests aimed at fostering regional cooperation, which counteracted provocative and objectively false claims of Ethiopia’s intentions from Somalia and some of his country’s regional rivals. Upon the successful completion of this deal, Ethiopia will be granted its own naval base in Somaliland, after which it’ll predictably search for regional partners with shared security interests.

Ethiopia previously enjoyed close relations with South Yemen during the Old Cold War so both would do well to explore the possibility of working closer together on maritime security in the modern day after the Ethiopian Navy is rebuilt. This could take the form of emulating the MoU in spirit whereby Aden via the STC could possibly consider offering docking rights to Addis on the mainland and/or Socotra in exchange for formally recognizing South Yemeni sovereignty whenever it’s formally redeclared.

Ethiopia’s boldness in agreeing to recognize Somaliland’s 1991 redeclaration of independence sets a positive precedent for recognizing South Yemen’s when the time comes and is why the STC should seriously consider establishing dialogue with Addis before then in order to best prepare for this. Taken together, established ties with the UAE and Russia coupled with potential ones with India and Ethiopia could lead to the STC indirectly expanding its influence in BRICS within which those four now participate.

In fact, independently of their potentially shared maritime security interests in South Yemen, they’re all already very close to one another to the point of forming an unofficial subgroup in that association. If the STC becomes yet another common denominator between them like is being proposed in this analysis, then they can individually and collectively do a lot for promoting its sovereignty cause. It’s here where the piece will now segue into the subject of how those four can help South Yemen in this way.

Soft Power Interests

Each of them brings something unique to the table in terms of soft power. The UAE commands a lot of influence in Arab countries, both in and of itself – including as a member of the Arab League – as well as via its media outlets, so it can help reshape popular opinion in favor of supporting the restoration of South Yemeni sovereignty. As for Russia, it wields similar influence over the entire non-Western world as a whole via RT and Sputnik, whose platforms can be leveraged in pursuit of complementary ends.

Meanwhile, India is the world’s largest democracy and the fast-growing major economy, which also declared itself the “Voice Of Global South” last year during two eponymous events and was accordingly recognized as such by those dozens of developing countries that participated in them. Its worldwide influence is surging as it becomes a globally significant Great Power and can be channeled through the aforementioned platform to promote the cause of South Yemeni sovereignty at an appropriate time.

Ethiopia’s influence might not be as broad as Russia’s and India’s, but it’s no less important in its own way. It’s the historical cradle of anti-imperialism on the continent and also hosts the African Union’s headquarters, thus imbuing it with immense influence over the entire landmass. Addis’s support of Somaliland’s redeclaration of independence, whose cause is kindred to South Yemen’s since both were recognized as sovereign states (Somaliland much less briefly in summer 1960), bodes well for Aden.

This bold move by Africa’s most influential country sets a positive precedent that could lead to Ethiopia championing South Yemen’s kindred cause in the event that Addis and the STC reach an agreement for docking rights on the mainland and/or Socotra as was earlier proposed. After all, South Yemen enjoyed sovereignty much longer than Somaliland did, and both now want to regain it after their own failed unity experiments. Ethiopia’s support of Somaliland could therefore translate to support for South Yemen.

Considering their similarities, as well as their shared interests via the UAE and possibly soon Ethiopia, the STC should also cultivate close bilateral ties with Somaliland. Not only is it a nearby nation so this makes sense for reasons of simple pragmatism, but its bold recognition of Taiwan could presage a similarly bold recognition South Yemen at the appropriate time, thus adding to its list of potential supporters. Furthermore, Somaliland wields influence disproportionate to its size, which could help South Yemen.

Last month’s scandal where Somalian-born Congresswoman Ilhan Omar was caught on tape suggesting that she prioritizes her homeland’s interests over those of America brought Somaliland’s cause to the forefront of American political attention and discourse. Although the US recognizes Somaliland as part of Somalia, some experts are newly inclined to encourage it to reconsider the wisdom of that policy. These figures could in turn become aware of South Yemen’s kindred cause via allied Somalilander influencers.

Although the STC is more than capable of promoting South Yemeni interests on its own, it’ll only help this cause if more countries do so as well, especially if they wield the unique influence that those four BRICS countries and Somaliland do in support of their shared interests. To recap, these are security-centric in light of the Red Sea Crisis but can form the basis for them to support the cause of South Yemeni sovereignty as a quid pro quo for reaching related maritime deals for docking and bases.

Concluding Thoughts

What’s being proposed is for the STC to creatively utilize the converging Red Sea and Horn of Africa Crises for the purpose of advancing South Yemen’s security, diplomatic, and soft power interests with a focus on clinching partnerships with the BRICS countries of the UAE, Russia, India, and Ethiopia. All four and Somaliland, with whom South Yemen shares a common Emirati partner, can do a lot for its cause. Hopefully these proposals will be dwelled upon by decisionmakers and tangible action taken on them.

Moscow-based American political analyst

* Opinions expressed in this analysis reflects its author