Archive

Last updated on: 14-08-2023 at 5 AM Aden Time

In the reign of Constantine, Aden was called the Romanum Emporium, owing to its commercial celebrity…a port worthy the acquisition and conquest of the Turks and Portuguese.

Fatimah Johnson (South24)

“On the 1st of Ramazan last (10 December 1836), I was appointed nakhooda [literally god of the ship in Persian, as in Captain] of a barque Doria Dowlut, of 225 tons, which vessel belonged to Begum Ahmed Nissa, mother of the present Nawab of Madras”. [1] Affidavit of Syed Nouradeen bin Jamal, Captain of the Doria Dowlut, 1 August 1837.

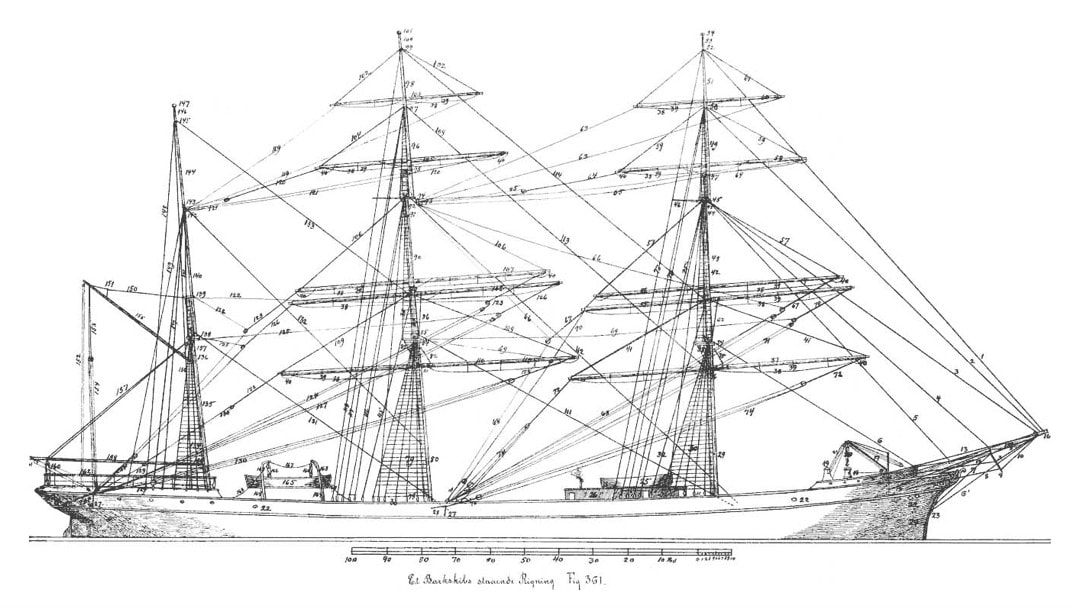

This seemingly routine occurrence, winning command of a barque, helped change the fate of Aden’s history. A barque is a large three mast ship with a unique sail plan. It dominated the Age of Sail, a three hundred year period that began around 1570. The Doria Dowlut was, in fact, on course from Calcutta to Jeddah not Aden. It was loaded with cargo having been freighted by an Arab merchant called Fridjee Ensof. The cargo included: rice, sugar, Bengali textiles, silk, shawls, kinkaub (Indian craftwork), parcels, two chests, preserves, brocades, cloth, rose perfume, ginger, pepper, coconut oil, Chinese satin, porcelain, copperware, lavender and jewelry . The ship, Doria Dowlut, was trading under British colours. Trading under British colours meant that it flew the British flag and was under British military protection. The Carnatic Sultanate, a vast kingdom in South India, in which Madras (now Chennai) was located, had come under the influence of Britain in the 1760s when the eleventh Nawab (King) by the name of Muhammad Ali Khan Wala-Jah was told by Sir John Lindsay (the plenipotentiary of George III of Britain) that the British King wished to protect him against all enemies even if that meant the English East India Company itself! [2]

“The Adeni people took the goods away from the ship but would not save the people. Among those people who escaped safely to the shore were some women. These they made naked, and searched for gold. They recognized me, Nouradeen, who was on the part of the Nawab, and they kept me forcibly under the water; but God preserved my life. I testify as to the acts of the people of Aden”. [3] Deposition of Syed Nouradeen and several other people on board the Doria Dowlut, undated.

The Doria Dowlut never reached the port of Jeddah and the nakhooda, Syed Nouradeen bin Jamal, along with other crew members, were instead subjected to a chilling ordeal that saw robbery, rape, bribery, assault, attempted murder, manslaughter and starvation occur after the barque was deliberately [4] wrecked off Aden on 20 February 1837. Those who survived this went on to be persecuted when they reached Mukha (Mocha) by an East India Company vakil (an agent). The vakil tried to have sex with the wife of a merchant who had been on board the ship. The merchant had been trying to make pilgrimage to Mecca. [5] There was also a significant number of other Muslim pilgrims, male and female, onboard the Doria Dowlut. In less than two years, Cape Aden was occupied by the Government of Bombay. The Government of Bombay had sought the permission of the Secret Committee of the Court of Directors of the East India Company to do so seven months after the Doria Dowlut was wrecked, on 26 September 1837. [6]

“…the Abdalees in Aden commenced firing on the British without provocation or warning”. [7] Letter by Captain Stafford Bettesworth Haines of the British Royal Navy to the Bombay Government, 13 December 1838.

The above referenced event was considered by Captain Haines as a “declaration of war” by the Chieftain of the Abdalee tribe and the Sultan of Lahj and Aden, Mohamed Houssian Fudthel against Britain. [8] Prior to this statement, the pillage of the Doria Dowlut had provoked the Government of Bombay (long under direct rule by the British Government with the passing of the East India Company Act of 1784) into claiming that the seizure of the port of Aden was justified as the British flag had been “insulted” when the Doria Dowlut was stolen from and the people of the ship were molested after running aground in Aden. A minute by Mr James Farish of the Bombay Government, accuses the Sultan of Lahj and Aden of taking part in the theft of the cargo along with the inhabitants of Aden. [9]

“‘Are the English so poor they can only afford one vessel? And she only came here to talk’”! [10] Letter sent from Aden by Captain Haines to the Secretary to the Bombay Government, 6 November 1838.

The above shows that the Sultan of Lahj and Aden had mocked peaceful attempts to agree a consensual transfer of Aden land and its harbour to the British. The letter goes on to quote Sultan Fudthel as having stated that if “the English” had sent many war ships and naval officers with no indication of entering into negotiations he would have ceded control of Aden immediately. In fact, sources from 1837 show that initially the Bombay Government had only wanted to secure a commercial agreement to set up a coal depot in Aden, effectively a giant coal shed with a few thousand tons of coal to power the new steam ships that marked a technical evolution in shipping and the ability to navigate through seasonal monsoons. [11] To this effect, Captain Haines had been sent to Aden on a steamer named Berenice around November 1837 with a letter to the Sultan Fudthel outlining the proposal from the Bombay Government. However, this offer was ultimately rejected following a series of discussions, correspondence, procrastination, capriciousness on the part of the Sultan, outright attempts to deceive and insult the British as Captain Haines perceived it. For example, at one point the Sultan Fudthel claimed his feet hurt too much for him to talk and later Captain Haines reminded him that he had not gone to Aden “to play”.

“You should consider that the British who are powerful both by sea and land, have a bond of your father for the land and harbour of Aden, and that bond must be fulfilled; but remember that the British though strong, are merciful, and do not oppress; and to convince you of the truth of what I assert, I send a copy of the treaty of transfer to which I require your signature”. [12] Letter by Captain Haines to Sultan Hamed, 31 October 1838.

The desperation of Captain Haines in the above to acquire a form of control over Aden is palpable. This desperation was not just caused by the series of direct insults by Aden but also by the dilemmas of the Ottoman Empire. In 1830 the Ottomans lost Greece, the Ottomans further suffered repeated military defeats by the Russians and in 1833 an invasion of Adana in what is now modern day Türkiye by their own viceroy, Muhammad Ali pasha. The weakening of the Ottoman Empire meant the British could not safely rely on it to guard against French and Egyptian competitiveness for greater domination over North Africa, the Arabian Peninsula, the Gulf, the Indian Ocean and the Red Sea. Napolean had frightened Britain in 1798 when he sent an expedition to Egypt and by the 1830s France had begun to dominate Algeria. Muhammad Ali pasha had occupied the Hijaz and Najd in 1833 in what is now the modern day Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. This heightened pressure from the west jeopardized “the security and prosperity of British India” [13]. It is interesting to note that the events that placed pressure on the British to forcefully capture Aden on 19 January 1839 predate the effort for diplomacy with Sultan Fudthel “for a coaling station on Aden’s Back Bay, to the west of the peninsula [that] would answer Britain’s essential needs and obviate a confrontation with Egypt”. [14]

“…he [Sultan Hamed] should write and explain everything to Sir Robert Grant and until his decision was known, I was to choose any spot I thought proper as a coal depot, and he would transfer it to the British under his seal”. [15] Captain Haines to the Superintendent of the Indian Navy, 20 January 1838.

Long established arguments about why Aden was seized on 19 January 1839 by the British Royal Navy have finally been challenged with the 2018 publication of Imperial Muslims by Scott S. Reese, who is also an expert in Islamic Africa. In the above letter Captain Haines wrote that the heir to the Sultanate of Aden and Lahj, (Hamed) verbally offered to cede control of Aden’s port in exchange for being an ally of the British, a guarantee of measures to prevent invasion of the Sultanate and an annual subsidy. Captain Haines avoided giving a response on this proposal by asking Sultan Hamed to contact Robert Grant, the governor of Bombay who along with the key figures in the Whig (a now defunct political party that had been established in 1679) government in Britain wanted the direct acquisition of Aden. [16] Superficially, this source appears to support the claim that there was a consensus among the British that they should blindly and obstinately construct a global network of territories (maritime and otherwise) and as such the seizure of Aden was a logical step and a step informed by the crude objective of inaugurating a coaling station to suit British purposes. The tendency to view all British imperial history as a neat story of selfishness and egotism is strong especially amongst those who are still bitter about the experience of British imperialism in the 20th century. [17] Moral offense though should not obscure what a more pensive and fuller reading of the relevant sources reveal. The sources in fact reveal that rather than a great vision for British world domination, the eventual motivation to occupy Aden was created by rational shared economic and political concerns: the trade of Indian and Arab merchants, the flow of capital, the frequent passage of ships into the Gulf of Aden and the Red Sea, relations with the Carnatic Sultanate which was still technically independent of British rule and relations with India’s huge Muslim population. [18] These concerns are encapsulated in the story of the Doria Dowlut. The sources also show that Captain Haines treated Syed Nouradeen bin Jamal and those who survived their ordeal very well when he came across them in Mukha and learnt of the abuse they had endured. He took down their statements, ensured their safety for two weeks and then had them transported to Bombay. [19] The de-villainization of British actions in Aden on 19 January 1839 will no doubt be shocking to many. Reese describes the story of the Doria Dowlut as reminiscent of Joseph Conrad’s literary works (the extreme dangers of life at sea) and firmly asserts the following: “It is a story of malfeasance, dereliction of duty and greed. It is also a tale of perseverance, bravery and compassion. The occupation of Aden was a direct consequence of its [the Doria Dowlut’s] deliberate grounding”. [20]

“In the reign of Constantine, Aden was called the Romanum Emporium, owing to its commercial celebrity…a port worthy the acquisition and conquest of the Turks and Portuguese…its scenery has been compared to Cintra [a beautiful town in Portugal]…it [Aden] is in fact perfect…”. [21] Brief remarks on Aden or Adden by Captain Haines, 1838, extract.

The understanding that Aden was only taken by force in 1839 to establish a coaling station has been the result of lazy, dismissive scholarship. Reese remarks in Imperial Muslims that rarely is the Doria Dowlut shipwreck given any credence in historical works about Aden and is almost always presented as a “thinly veiled pretext that served to cover their [the British] true motive”. [22] In the extract just above, Captain Haines writes lovingly of Aden, he writes of a desire to restore its former commercial glory, of a desire to implement morally correct laws and system of government. He claims that the Sultan of Aden was an oppressor of all especially the poor of Aden, who levied taxes on everything and who had provoked the Futhelee tribe into ransacking Aden in 1836 of thirty-thousand dollars. This information, along with what is known about the Doria Dowlut shipwreck, does not square with the solipsistic coaling station hypothesis about British motives. What also falls outside of the coaling station hypothesis, is Aden’s imagined cosmic connection and her historical connection to India that reaches back a thousand years before British rule. In the thirteen century, common era, the traveller Ibn al-Mujawir wrote in a travelogue that there is a tunnel in Sira island in Aden’s harbour that connects directly to what is now modern day Madhya Pradesh in central India. Ibn al-Mujawir’s travelogue states that the Hindu god Hanuman excavated the tunnel to rescue Sita of Ramayana fame who had been abducted by a demon called Hadathar from ancient Malwa in India and taken to Aden. Hanuman tunnels during the space of one night, finds Sita asleep beneath a thorn tree in Aden, throws her on his back and transports her through the tunnel to India [23]. There are many other examples of Arab literature that sought to magnetize Aden to India by maintaining that there existed a supernatural pull between the two. Reese writes that the efforts to pencil this magical connection was due to the enduring influence of the Hellenistic ideal of creating a Greater Hind that would incorporate Arabia. In other more commonplace narratives about the relationship between Aden and India, the social, political, economic, religious and genealogical links between the two are highlighted. Reese’s underlying point is that Aden and India had been conjoined entities for at least a thousand years: “…the establishment of the Aden Settlement in 1839…was only the most recent iteration of Indian Ocean imaginary that stretched back centuries” [24]. The doomed voyage of the Doria Dowlut that struck one of Aden’s reefs at 3 a.m. on 20 February 1837 was the sounding bell for yet another hallowed communion between Aden and India albeit this time facilitated by the British.

[1] Accounts and Papers of the House of Commons, Indian Papers – Correspondence relating to Aden Volume 11 of 21 Volumes - Volume 40, Oxford University: Bodleian Library, 30 May 1839, No.9

[2] Ramaswami, N.S. Political History of Carnatic Under the Nawabs, Abhinav Publications, 1984, p.215

[3] Accounts and Papers of the House of Commons, Indian Papers – Correspondence relating to Aden Volume 11 of 21 Volumes - Volume 40, Oxford University: Bodleian Library, 30 May 1839, No.7

[4] Reese, Scott S. “Aden, the Company and Indian Ocean Interests.” Imperial Muslims: Islam, Community and Authority in the Indian Ocean, 1839–1937, Edinburgh University Press, 2018, p.97

[5] Reese, Scott S. “Aden, the Company and Indian Ocean Interests.” Imperial Muslims: Islam, Community and Authority in the Indian Ocean, 1839–1937, Edinburgh University Press, 2018, p.105

[6] Accounts and Papers of the House of Commons, Indian Papers – Correspondence relating to Aden Volume 11 of 21 Volumes - Volume 40, Oxford University: Bodleian Library, 30 May 1839, No.18

[7] Accounts and Papers of the House of Commons, Indian Papers – Correspondence relating to Aden Volume 11 of 21 Volumes - Volume 40, Oxford University: Bodleian Library, 30 May 1839, No.101

[8] Accounts and Papers of the House of Commons, Indian Papers – Correspondence relating to Aden Volume 11 of 21 Volumes - Volume 40, Oxford University: Bodleian Library, 30 May 1839, No.101 & No.129

[9] Accounts and Papers of the House of Commons, Indian Papers – Correspondence relating to Aden Volume 11 of 21 Volumes - Volume 40, Oxford University: Bodleian Library, 30 May 1839, No.49

[10] Accounts and Papers of the House of Commons, Indian Papers – Correspondence relating to Aden Volume 11 of 21 Volumes - Volume 40, Oxford University: Bodleian Library, 30 May 1839, No.61

[11] Stookey, Robert W. South Yemen, A Marxist Republic in Arabia, Routledge, New York, 2019, p.32

[12] Accounts and Papers of the House of Commons, Indian Papers – Correspondence relating to Aden Volume 11 of 21 Volumes - Volume 40, Oxford University: Bodleian Library, 30 May 1839, No.69

[13] Stookey, Robert W. South Yemen, A Marxist Republic in Arabia, Routledge, New York, 2019, p.32

[14] Stookey, Robert W. South Yemen, A Marxist Republic in Arabia, Routledge, New York, 2019, p.32

[15] Accounts and Papers of the House of Commons, Indian Papers – Correspondence relating to Aden Volume 11 of 21 Volumes - Volume 40, Oxford University: Bodleian Library, 30 May 1839, No.21

[16] Stookey, Robert W. South Yemen, A Marxist Republic in Arabia, Routledge, New York, 2019, p.32

[17] Aydin, Cemil, The Idea of the Muslim World: A Global Intellectual History, Harvard University Press, 2017, p.146

[18] Reese, Scott S. “Aden, the Company and Indian Ocean Interests.” Imperial Muslims: Islam, Community and Authority in the Indian Ocean, 1839–1937, Edinburgh University Press, 2018, p.97 & p.107

[19] Accounts and Papers of the House of Commons, Indian Papers – Correspondence relating to Aden Volume 11 of 21 Volumes - Volume 40, Oxford University: Bodleian Library, 30 May 1839, No.9

[20] Reese, Scott S. “Aden, the Company and Indian Ocean Interests.” Imperial Muslims: Islam, Community and Authority in the Indian Ocean, 1839–1937, Edinburgh University Press, 2018, p.97

[21] Accounts and Papers of the House of Commons, Indian Papers – Correspondence relating to Aden Volume 11 of 21 Volumes - Volume 40, Oxford University: Bodleian Library, 30 May 1839, No.153

[22] Reese, Scott S. “Aden, the Company and Indian Ocean Interests.” Imperial Muslims: Islam, Community and Authority in the Indian Ocean, 1839–1937, Edinburgh University Press, 2018, p.97

[23] Reese, Scott S. “Hanuman’s Tunnel: Collapsing the Space between Hind and Arabia in the Arab Imaginary.” Imperial Muslims: Islam, Community and Authority in the Indian Ocean, 1839–1937, Edinburgh University Press, 2018, p.44

[24] Reese, Scott S. “Hanuman’s Tunnel: Collapsing the Space between Hind and Arabia in the Arab Imaginary.” Imperial Muslims: Islam, Community and Authority in the Indian Ocean, 1839–1937, Edinburgh University Press, 2018, p.82

Previous article

Next article