Last updated on: 16-08-2021 at 2 PM Aden Time

Andrew Korybko | South24

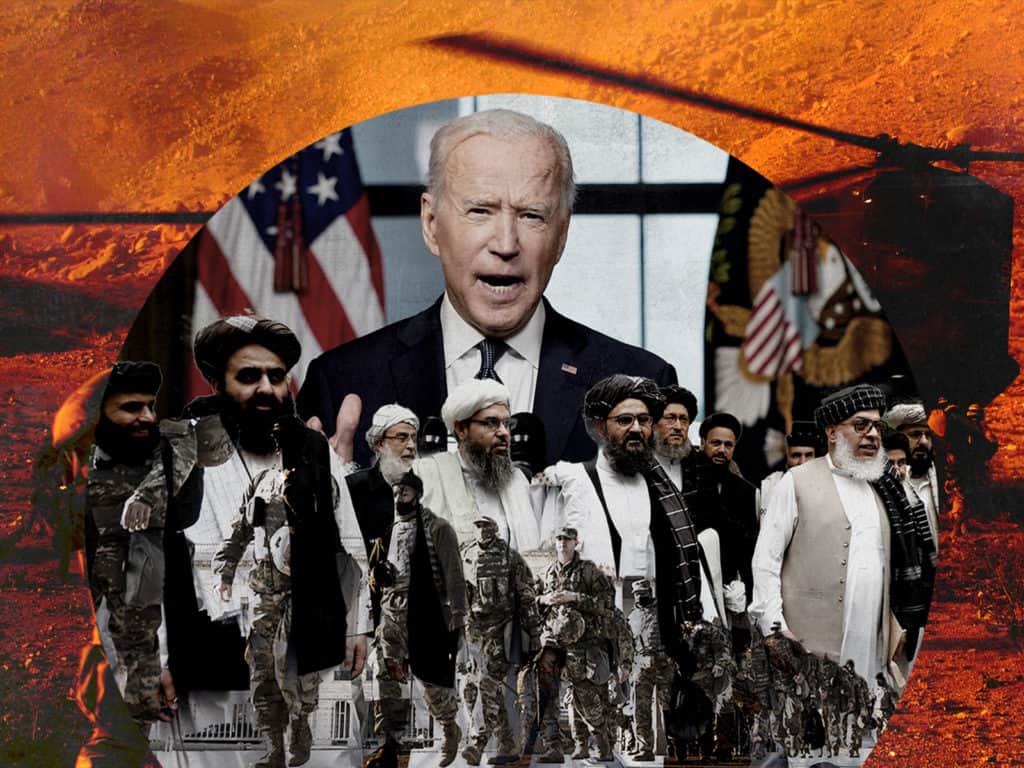

The Taliban's successful blitz across Afghanistan surprised most observers who hadn't expected America's allies there to collapse so quickly, let alone within less than two weeks since the group started its spree of capturing regional capitals. This dramatic development will have far-reaching geostrategic consequences, but of particular interest is how it might influence events in West Asia. This dimension has been under-studied but is no less important than the consequences that the Taliban's Afghan takeover will have on Central and South Asia.

Firstly, America's Arab allies might no longer regard Washington as a reliable guarantor of their security. Not only has US President Biden put pressure on his country's traditional Saudi ally to scale down and ultimately stop its ongoing operations in Yemen, but he just abandoned America's Afghan allies to the Taliban despite that group having been one of his government's worst enemies for the past two decades. This suggests a cold approach to regional geopolitics where perceived national interests trump morals, ethics, values, and optics.

The US' presumed interests in West Asia nowadays largely rest in renegotiating the Iranian nuclear deal, to which end America might be willing to make backroom deals with the Islamic Republic. The Biden Administration believes, whether rightly or wrongly, that it should revive the regional policy of its Obama-era predecessors in restoring a sense of balance to America's strategy there. Instead of always supporting its traditional Arab allies out of principle, it's willing to compromise on their interests to improve ties with Tehran.

If this assessment is accurate, and the Biden Administration's approach to Yemen suggests that there's some veracity to this observation, then it might be inevitable that the outcome of that war-torn country's conflict could be largely determined through a backroom deal with Iran. In particular, Washington might support the Houthis being cautiously welcomed into the international community as legitimate political stakeholders similar to how it nowadays treats the Taliban in Afghanistan.

Regardless of how pragmatic of a policy one might believe this to be, it would arguably be against the stated interests of the Saudi-led coalition and could lead to a “loss of face” there similar to what the internationally recognized government in Afghanistan just experienced. Some in Kabul accused the US of going behind their back to legitimize the Taliban without first consulting the country's authorities and even sometimes pressuring them to comply with their ally's efforts to this end such as through the contentious release of Taliban prisoners.

Along the same lines, the US might soon ramp up its pressure on Saudi Arabia to do something similar following the precedent that it's just pioneered in Afghanistan, though this time for the purpose of improving relations with Iran through their speculative backroom deal on Yemen aimed at advancing the Iranian nuclear renegotiation process. Without being assured of their American ally's full support, which was already questionable ever since Biden entered office and changed the US' policy, Riyadh might have to compromise.

Put another way, what just happened in Afghanistan might not be a fluke of American policy but the beginning of an entirely new approach for resolving seemingly intractable regional conflicts. The emerging model might be that the US is willing to trade its allies' interests in order to advance its own perceived national ones at their expense. In Afghanistan, this led to accusations of selling out Kabul in order to rapidly redeploy US forces there to the Asia-Pacific in order to contain China, while in Yemen it might be related to the Iranian nuclear deal.

The internationally recognized Afghan government was powerless to push back against this American scheme since it had earlier failed to independently diversify its security stakeholders. India couldn't ever meaningfully intervene in any conventional sense for obvious geopolitical reasons related to its inability to transit through neighboring Pakistan's airspace while Iran was unable to do much since it was too embroiled in proxy wars elsewhere in West Asia. Moreover, the Taliban swiftly captured all border outposts to cut off any proxy support.

In the Yemeni context, Saudi Arabia is also struggling to independently diversify the security stakeholders in its campaign. The UAE's military drawdown a few years back pretty much left the Kingdom to fend for itself in the northern part of the country. It's true that some South Yemeni forces still fight against the Houthis as part of the coalition's efforts, but it's not the same as when Abu Dhabi was more actively engaged in the conflict there. This development coupled with Biden's new policy towards the war put significant pressure on Saudi Arabia.

Riyadh must therefore expect the worst just in case and thus prepare for Washington to abandon it even more in Yemen than it already has just like it abandoned its allies in Kabul earlier this month. Generally speaking, the US wants to refocus the vast majority of its military efforts on the Asia-Pacific in order to contain China, but it might also have a more specific regional goal in Yemen related to striking a backroom deal with Iran there as part of a possible compromise related to advancing the nuclear deal's renegotiation process.

From the perspective of the Yemeni War's various stakeholders, this is both an obstacle and an opportunity. The Saudis would understandably see this as the worst-case scenario since it could result in a similarly humiliating diplomatic defeat there as the one that the internationally recognized Afghan government just experienced. The Houthis would obviously regard this as an opportunity to legitimize their control over the North, which aligns with Iranian interests, while STC might see a chance to legitimize its own control over the South.

To explain the last point, the STC should expect the US to be even more flexible in its stance towards the Yemeni War than before after the latest events in Afghanistan suggested the emergence of a new American model for resolving seemingly intractable conflicts. The most pragmatic compromise that the US might make with Iran would be to formalize Yemen's de facto internal partition through a Bosnian-like confederal model, even if only an interim one pending a new constitution.

This would enable the Houthis to entrench their own sphere of influence over the North just like the STC could do the same over the South. The international dimensions of this possible compromise are that Iranian and Emirati interests respectively would be met while the Saudi ones would be sacrificed on this geostrategic altar. In fact, the intra-GCC power dynamic could continue shifting in the direction of the UAE becoming more regionally influential than Saudi Arabia, including as America's comparatively more preferred ally.

The Biden Administration might not just conceptualize this as a more pragmatic regional strategy, but perhaps also as an unstated act of revenge for the Kingdom's support of former President Trump. Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman was very close with Trump's son-in-law Jared Kushner, yet Saudi Arabia's highly publicized investments in influencing American policy are all now for naught and might even in hindsight be seen as counterproductive because of the domestic US perception of Riyadh as a partisan actor in US politics.

The UAE, by contrast, was always very careful to not be seen as too close to one or another US administration but just as an American ally in general. It could very well be that Abu Dhabi might be rewarded for this pragmatism through Washington's possible efforts to promote a confederal solution to the Yemeni War (even if only an interim one) premised on its newfound interests in rebalancing its regional policy, improving ties with Tehran through backroom deals, and possibly also taking revenge against Saudi Arabia for supporting Trump.

Moscow-based American political analyst

Photo: GettyImages