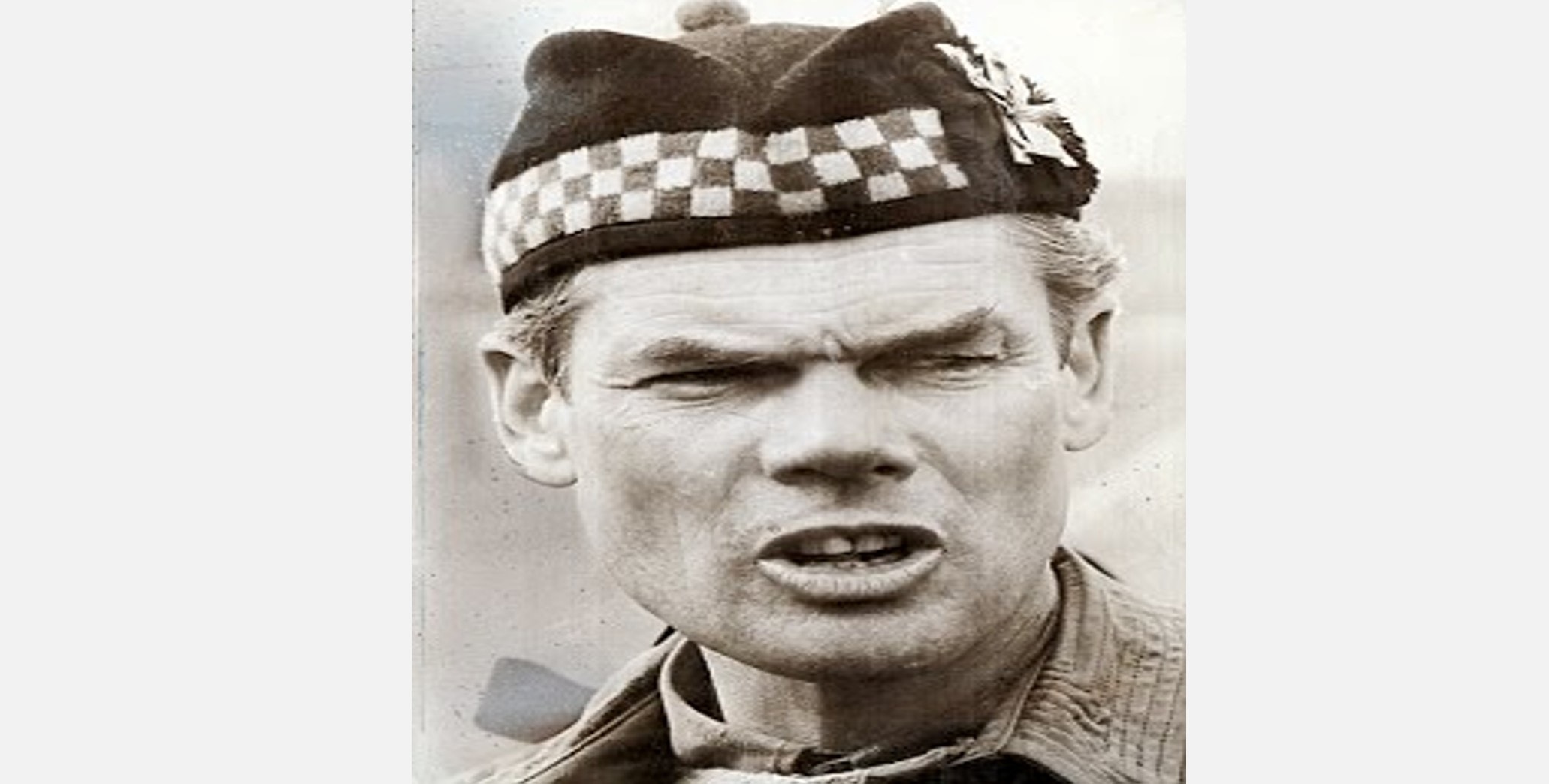

Photo: Mad Mitch (Archive, edited by "South24")

Last updated on: 01-05-2023 at 11 AM Aden Time

By Fatimah Johnson (South24)

The Mr Hyde of the British Empire was Lt Colonel Colin Mitchell also known as “Mad Mitch”. Mitchell was the Commanding Officer of Aden from June to November 1967. He led the 1st Battalion Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, roughly one thousand men, who under Mitchell attacked Aden at 7pm on 3 July 1967. Mitchell informed British Independent Television News (ITN) that he “had to go back in [to Crater]” and that “the whole prestige of the [British] Army depended on going back in”.[1]

Prior to a key date in South Yemen’s history, that is 20 June 1967, Britain through its Colonial Office in Whitehall, London, its various Governors, Commanders in Chief, High Commissioners, Captains, Majors and Middle East Command ruled Aden and its hinterland via a heavy dependence on trooping, mounted guns, vessels of war and defensive walls.[2] Collaboration and consent at certain levels had also in part made British rule possible in Aden. However, by 1963, South Yemenis finally made consistent use of two precious faculties – “the power to think and the desire to rebel”.[3]

The conventional wisdom of cause and effect is that Egypt’s President Gamal Abdul Nasser’s insistence from 1956 onwards that the British retreat from Aden, led to the Radfan Uprising of 1963.[4] However, the truth is that sections of the South Yemeni population had rebelled against British troops since Captain Smith of the Royal Navy and Major Bailie had successfully stormed Aden on 19 January 1839.[5] There was agitation against the British even during the storming of Aden (island, town and pass) and 12 South Yemenis were killed by the British during an affray.[6] Fifteen British officers were killed during the capture of Aden and the loss to South Yemenis was described by the British as “very severe”.[7] Prior to the storming, Captain Stafford Bettesworth Haines had described the actions of the Sultan of Lahj, M. Houssian Fudthel, as a “declaration of war against the English”.[8]

The writer’s mother recalled seeing Mitchell on patrol in Crater in Aden, completing menial tasks like non intelligence-based security checks and he would even censure South Yemenis for driving too fast.[9] Mitchell appears to have shared much in common with Captain Haines. Mitchell revelled in the act of infantilizing South Yemenis according to ITN reporter Alan Hart.[10] This is much like the patronising attitude Captain Haines had towards them in the 19th century, as is revealed by the Indian papers of the British House of Commons whether they were private individuals or royalty. Mitchell was violent too. He appeared to have no regard for the universal non-derogable binding obligations on him as part of a belligerent occupying force under international humanitarian law such as the Hague Convention IV 18 October 1907 and the Fourth Geneva Convention 12 August 1949. He casually spoke about blowing the heads off of people, being “mean” and killing anyone who was deemed to be using violent methods themselves.[11] This is in contravention of Articles 27, 31 and 32 of the Fourth Geneva Convention which forbids all acts of violence and threats thereof, physical/moral coercion and physical suffering.[12]

A review of Mitchell’s autobiography, Having Been A Soldier (1969) reveals his mindset: he was concerned primarily with his prowess as a soldier. His autobiography begins with the following quote; the consequences for political manoeuvres and human rights in South Yemen are clear:

Every man thinks meanly of himself for

not having been a soldier, or not

having been to sea.[13]

Dr Johnson is recorded in Boswell’s Life of Samuel Johnson LL.D as claiming, that if any person were made to choose between the warrior king Charles XII of Sweden, hand on sword and Greek philosopher Socrates offering a lecture, they would be ashamed to follow the man who inspired Meno of Plato.[14] It would seem that Mitchell would agree with this assessment and this led to his actions in re-occupying Aden.

It was the British press that gave Mitchell his moniker of “Mad Mitch”. This decision appears to attest to Mitchell’s love of violence and the mass media’s corresponding love. Mitchell once described himself as “purely a soldier”[15] when explaining why he led the re-occupation of Aden and decades later in an article from 2008 he is described in the British newspaper, The Daily Record, as a “warrior”, and his alleged “bravery” is noted and it is claimed that the British general population “loved” him.[16] This is despite the fact that the same article records how Mitchell compared killing 4 South Yemenis to the ease of killing grouse. Grouse are game birds which are shot needlessly in Britain as a type of so-called sport – a horrific practice that is yet to be banned by the British Parliament: “It was like shooting grouse, a brace here and a brace there”.[17]

The reporter Alan Hart of ITN attests to what was tantamount to a media-military alliance to soften Mitchell’s image and downplay the instances of theft, torture, assault and the killing of South Yemenis by British troops.[18] It may be that the word mad was used to describe Mitchell to position him as a sort of romantically mad hero figure to cover up the reality of the methods used in Aden by the British. The reality was that the battalion who preceded the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders (the Royal Northumberland Fusiliers) in Aden, freely admit that they regarded South Yemenis as “gollies”[19] and when Mitchell himself was asked if he was a commanding officer at the turn of the 19th century rather than in 1967 his objectives would have been clearer, he replied, “You mean I would have been a nigger bashing imperialist”.[20]

Mitchell’s behaviour speaks to a historic refusal by the British to respect independent nationalist aspirations in the region. In January 1963, ruling elites in the Aden Protectorates agreed to unifying surrounding territory with the subjugated colony of Aden.[21] Thus, the Federation of South Arabia (FSA) was constituted even though the British were well aware of agitation for an independent sovereign South Yemen. In addition, even when the British government of the day in 1964, declared it would withdraw from the FSA by 1968, they wished to keep some British troops in the country.[22] They also sought to hand power over to the constituent parts of the FSA[23] rather than a referendum being held to gauge who the public really wanted to rule in South Yemen. Duncan Sandys, British Secretary of State for Commonwealth Relations and the Colonies, 1960 to 1964, stated that he saw Aden as a matter of convenience to Britain when he said in 1962:

In statements on colonial policy, it has become fashionable to mention everybody else's interests except our own. Some people seem to think that it is almost improper to suggest that Britain, too, may at times have interests which ought to be safeguarded. Our military base at Aden is a vital stepping stone on the way to Singapore.[24]

It is in this context of the above outlined cavalier attitude, that on 10 December 1963 a grenade was lobbed at Aden Airport. The British High Commissioner, some Ministers and officials were there, about to leave for constitutional talks in London.[25] Following this incident, a British member of Parliament for The Wrenkin (William Yates) openly talked in the House of Commons about South West Arabia as though it were a plaything and touted the idea that the British might consider a new policy for forming a “Greater Yemen”.[26]

When the “day of black tragedy in South Arabia, with a waste of British and Arab lives”[27] took place on 20 June 1967, Britain responded with force as it sought to keep South Yemen its prisoner. On 20 June 1967, 10 British servicemen were killed as FSA police officers turned their guns on them and seized government buildings in the then capital of Al Ittihad. Lord Shackleton informed the House of Commons that: "When darkness fell the British forces were withdrawn to positions surrounding Crater rather than in it”.[28]

Mitchell could not have been in any doubt that forces like the National Liberation Front (NLF) and Front for the Liberation of Occupied South Yemen (FLOSY) etc. and ordinary members of the South Yemen population wanted political freedom. However, he chose to attack Aden (Operation Stirling Castle) under the cover of dark like a coward whilst Scottish music was played by Pipe Major Kenneth Robson. Amnesty International’s report of 1966 detailed that the British had used torture in Aden including removing detainees’ clothes and interrogating them naked, hitting their genitals, stubbing out cigarettes on their skin, making them sit on poles directed at the anus and sleep deprivation.[29] Mitchell’s amorality towards such outrages and his hubris is confirmed when it is revealed that of the Scottish music played during the re-occupation of Crater, he commented that it was worth all his “quarter century of soldiering”.[30]

In one interview, Mitchell reveals that he advocated what can only be described as endless occupation.[31] He states in the interview that he wished to stay with his battalion as long as the British were in Aden. Despite the eventual withdrawal of the British from Aden in November 1967, research of the UK’s National Archives by historian Mark Curtis has revealed that ongoing covert operations were being planned for the post-independence period.[32] The records from the National Archives refer to an operation called “Rancour II”. They further state that a British embassy in the independent South Yemen or a military mission could be used as a cover for covert action.[33] It seems likely that Mitchell shared the view that South Yemenis could be so easily duped. He stated that his traditional Scottish headgear decorated with ribbons and a pom-pom which he wore as part of his military dress (the Glengarry bonnet) would help South Yemenis to “get the message”[34] that any resistance would result in his use of fatal violence – they would “get their head blown off”.[35] It is to be acknowledged that Curtis in his book, Unpeople: Britain’s Secret Human Rights Abuses notes that most files related to covert British operations in the liberated South Yemen have been censored. However, as the Italian philosopher, Benedetto Croce states, history when properly understood does not have to be anxious about “not being able to know that which is not known, only because it was or will be known”.[36]

Following South Yemen’s staggering political nationalist victory over Britain in late 1967, Mitchell claimed in an interview that he and his troops needed no exoneration.[37] Despite saying this he looks down from the camera guiltily as though haunted by what the British newspaper, the Evening Standard, described as a “forced truce”.[38] Credible source material shows South Yemenis placed by British soldiers in concentration camps behind barbed wire.[39] Torture though, did not prevent the “biggest UK defeat”[40] in British history (next is the recent Afghanistan debacle), and Mitchell was then punished by his home establishment. He was lionized for a short time on return to the UK. Video footage depicts him guzzling sparkling white wine whilst wearing a black bow tie, red waistcoat and a kilt.[41] In time though he was scorned by his political masters and denied promotion in the British Army. He resigned in 1968 and died in 1996 to join the ghosts of the South Yemenis he killed. Mitchell should have known what Shakespeare’s doomed triumvir; Mark Antony knew so well: “Kingdoms are clay”.[42]

Fatimah Johnson

A citizen journalist based in the United Kingdom

Photo: Mad Mitch (Archive, edited by "South24")

References:

[1] British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) Two, Empire Warriors – Mad Mitch and His Tribal Law, Episode 1: Friday 19 November 2004

[2] Captain Hunter, F.M, An Account of the British Settlement of Aden in Arabia, London, Trübner & Co, 1877, pp 141-145

[3] Bakunin, Mikhail, God and the State, New York: Dover Publications Inc, 1970, p9

[4] New York Times, NASSER’S GROWING CONCERN OVER YEMEN; U.A.R Leader’s Visit Indicates the Importance Of the Area to His Arab World Ambitions, Section E: May 3 1964, p5

[5] iwm.org.uk

[6] Accounts and Papers of the House of Commons, Indian Papers – Correspondence relating to Aden Volume 11 of 21 Volumes - Volume 40, Oxford University: Bodleian Library, 30 May 1839, No.131

[7] Accounts and Papers of the House of Commons, Indian Papers – Correspondence relating to Aden Volume 11 of 21 Volumes - Volume 40, Oxford University: Bodleian Library, 30 May 1839, No.128

[8] Accounts and Papers of the House of Commons, Indian Papers – Correspondence relating to Aden Volume 11 of 21 Volumes - Volume 40, Oxford University: Bodleian Library, 30 May 1839, No.129

[9] BBC Two, Empire Warriors – Mad Mitch and His Tribal Law, Episode 1: Friday 19 November 2004

[10] BBC Two, Empire Warriors – Mad Mitch and His Tribal Law, Episode 1: Friday 19 November 2004

[11] BBC Two, Empire Warriors – Mad Mitch and His Tribal Law, Episode 1: Friday 19 November 2004

[12] Amnesty International, Iraq - Responsibilities of the occupying powers, AI MDE/14/089/2003 Index April 2003

[13] Boswell, James, Life of Samuel Johnson LL.D, 10 April 1778

[14] Kilbourne, H.R, Dr Johnson And War, John Hopkins University Press, June 1945, p130

[15] BBC Two, Empire Warriors – Mad Mitch and His Tribal Law, Episode 1: Friday 19 November 2004

[16] dailyrecord.co.uk

[17] dailyrecord.co.uk

[18] BBC Two, Empire Warriors – Mad Mitch and His Tribal Law, Episode 1: Friday 19 November 2004

[19] BBC Two, Empire Warriors – Mad Mitch and His Tribal Law, Episode 1: Friday 19 November 2004

[20] BBC Two, Empire Warriors – Mad Mitch and His Tribal Law, Episode 1: Friday 19 November 2004

[21] nam.ac.uk

[22] nam.ac.uk

[23] nam.ac.uk

[24] api.parliament.uk

[25] api.parliament.uk

[26] api.parliament.uk

[27] api.parliament.uk

[28] api.parliament.uk

[29] theguardian.com

[30] thehistoryherald.com

[31] BBC Two, Empire Warriors – Mad Mitch and His Tribal Law, Episode 1: Friday 19 November 2004

[32] Curtis, Mark, Unpeople: Britain’s Secret Human Rights Abuses, UK: Vintage, 2004, p.301

[33] Curtis, Mark, Unpeople: Britain’s Secret Human Rights Abuses, UK: Vintage, 2004, p.301

[34] BBC Two, Empire Warriors – Mad Mitch and His Tribal Law, Episode 1: Friday 19 November 2004

[35] BBC Two, Empire Warriors – Mad Mitch and His Tribal Law, Episode 1: Friday 19 November 2004

[36] Croce, Benedetto, Theory & History of Historiography, (Trans. by Douglas Ainslie) London: George G. Harrap, 1921, p.50

[37] BBC Two, Empire Warriors – Mad Mitch and His Tribal Law, Episode 1: Friday 19 November 2004

[38] Granada Television, End of Empire, Chapter 9: Aden 1985

[39] Granada Television, End of Empire, Chapter 9: Aden 1985

[40] twitter.com

[41] BBC Two, Empire Warriors – Mad Mitch and His Tribal Law, Episode 1: Friday 19 November 2004

[42] Shakespeare, William, Antony and Cleopatra, Boston, USA: Ginn & Company, 1888, Act I, Scene I.

Next article