The Adenite Jewish community in 1950s Aden (Credit: Fatimah Johnson)

Last updated on: 01-05-2023 at 11 AM Aden Time

Fatimah Johnson (South24)

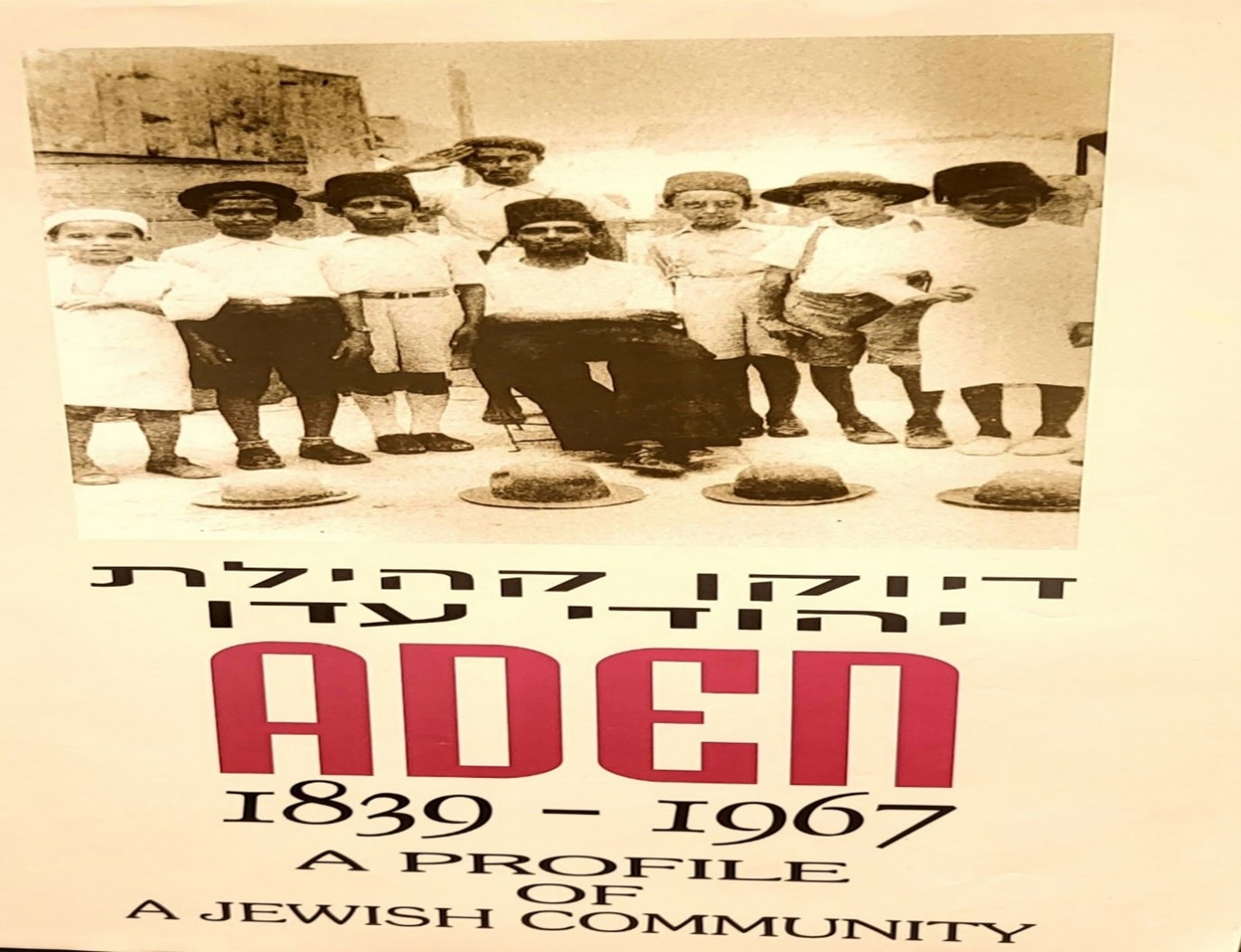

“I would love to come to visit [Aden] – tomorrow morning!” These are the words of Dani Goldsmith, an Israeli Adeni descendant whose life is rooted in Tel Aviv. His maternal grandparents, Moses and Esther, were Adeni Jews who left Aden for Mandatory Palestine in 1924. Today Esther’s name is emblazoned high on the facia of the Hotel Cinema (a former cinema turned hotel that she and Moses established in Zina Dizengoff Square, Tel Aviv). Dani Goldsmith is directly related through this set of his grandparents to the Menahem Messa family, who via their extreme wealth had great political power over Jewish life in Aden. The family’s investment in Aden was high (synagogues like the Mualama Al Kabira/Magen Avaraham, schools, printing presses, a major trading company, real estate, poor houses etc..). [1]

The Hotel Cinema in Tel Aviv (Credit: Fatimah Johnson)

Their continued affection and affiliation to Aden is also high and led to the creation of the Aden Jewish Heritage Museum at 5 Lilienblum Street, Tel Aviv, some 10 years ago by Dani Goldsmith and his cousin. The foci of the museum’s curation are the sociological, healthy doses of Anglophilia, nostalgia, Judaica and chronological Adeni Jewish history. For an Adeni descendant like myself (though non Jewish) the effect of some of the exhibits is utterly heart-warming. Items typical of an Adeni woman’s kitchen are showcased like grinding stones (a mathana in the singular) and vast aluminium pockmarked pots (a dest in the singular) that could have cooked a signature Adeni meal, zurbiyan (a lush dish of South Indian Hyderabadi origin that requires extensive preparation, still much loved by modern South Yemenis).

Inside the Tel Aviv Museum (Credit: Fatimah Johnson)

The exhibits' atmosphere is also electrifying. The exhibits feel like forbidden fragments of an obscured Adeni history. It could be said that in its own small way, the museum helps to assuage the general reluctance to see the Middle East (an area roughly the size of the United States of America) as a pluralistic meta-region and the alarming ease with which Arabs are seen as “naturally” anti-Semitic.

A Tik (Torah case) (Credit: Fatimah Johnson)

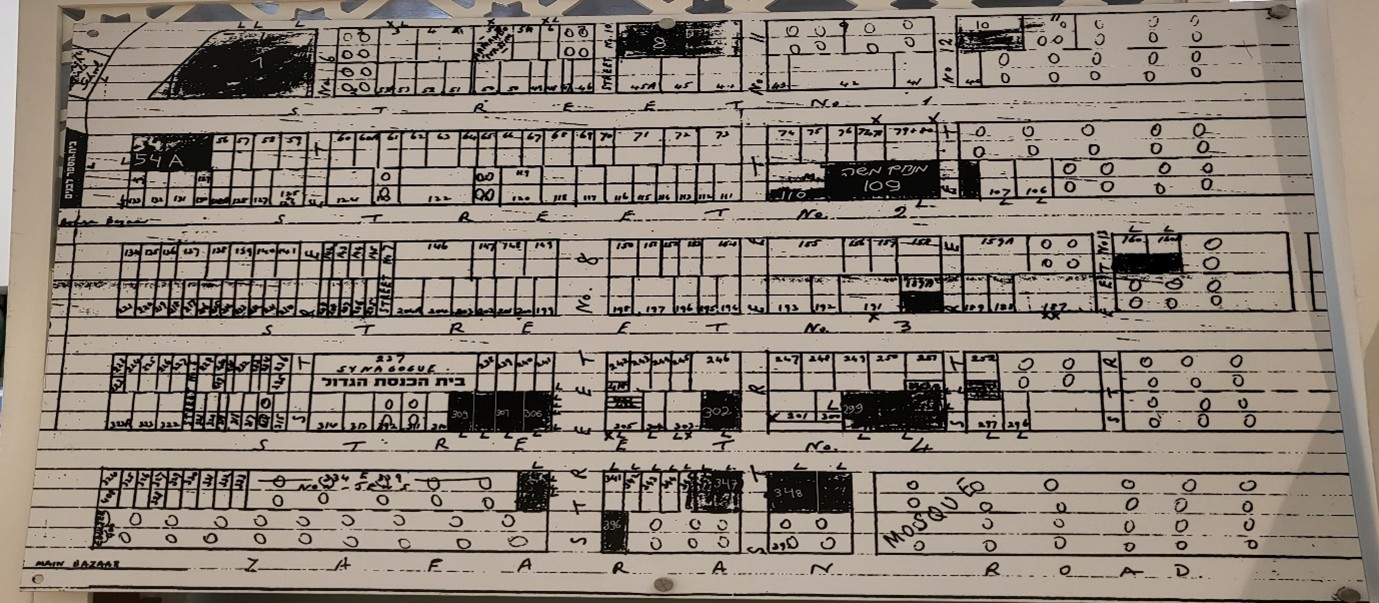

The tumultuous events in the pan Yemeni region from the 1960s onwards have hitherto suffocated Aden’s remarkable and distinct stories of which the Jewish story is one. Writing in 1994, the Israeli academic, Reuben Ahroni described Aden as having a “unique cosmopolitan kaleidoscopic nature”. [2] Details about the Jewish Aden, show that the community was dynamic and creative. They created a Judeo-Arabic dialect that also borrowed words from Gujarati, Persian, Somali, Greek, Hindi, English, Turkish, Arabic and Hebrew. [3] They established a living district in Aden Crater within the extinct volcano and gave colorful (but unofficial) names to its streets: Chaphat Al Hamra (Red street), Chaphat Banin, Chaphat Al Chobz (Bread street), Chaphat Al Mullah and Chaphat Zafaran (Saffron street). [4]

Diagram of the Jewish Quarter in Aden (Credit: Fatimah Johnson)

A stubborn myth about Yemen (North and South) is that it is the origin of the Arab people. This is despite the fact that Semitic is a linguistic classification not a racial one. This myth speaks to a deliberate attempt to cover up what should be obvious about the two Yemens – that they have always been hybrid countries rather than homogeneously Arab. A common political elephant in the room in any discourse about the Middle East, is its Jewishness both before the “miracle” [5] of Israel (to borrow Edward Said’s own words) and since. Almost any discussion about the Middle East’s Jewish components is seen as “emotional”. [6] This is a word that George Orwell said, in a 1945 essay, was code for nationalism, “a habit of mind that affects our thinking on nearly every subject”. [7] To Orwell, nationalism was the habit of classifying human beings like insects and identification with a nation or other unit that is seen as beyond good and evil. [8] The attitude that Jewish presence in the Arab world is an emotional subject is designed to suppress candid discussion about the Middle East’s history, contemporary or otherwise. It seems that like Shylock’s accusation to Bassanio in The Merchant of Venice, when dealing with the narrative of the Middle Eastern universe, you are expected to please people with your answers. [9] The objective world though, produces very different and even revelatory answers.

An exhibition poster from the Tel Aviv Museum, 1994 (Credit: Fatimah Johnson)

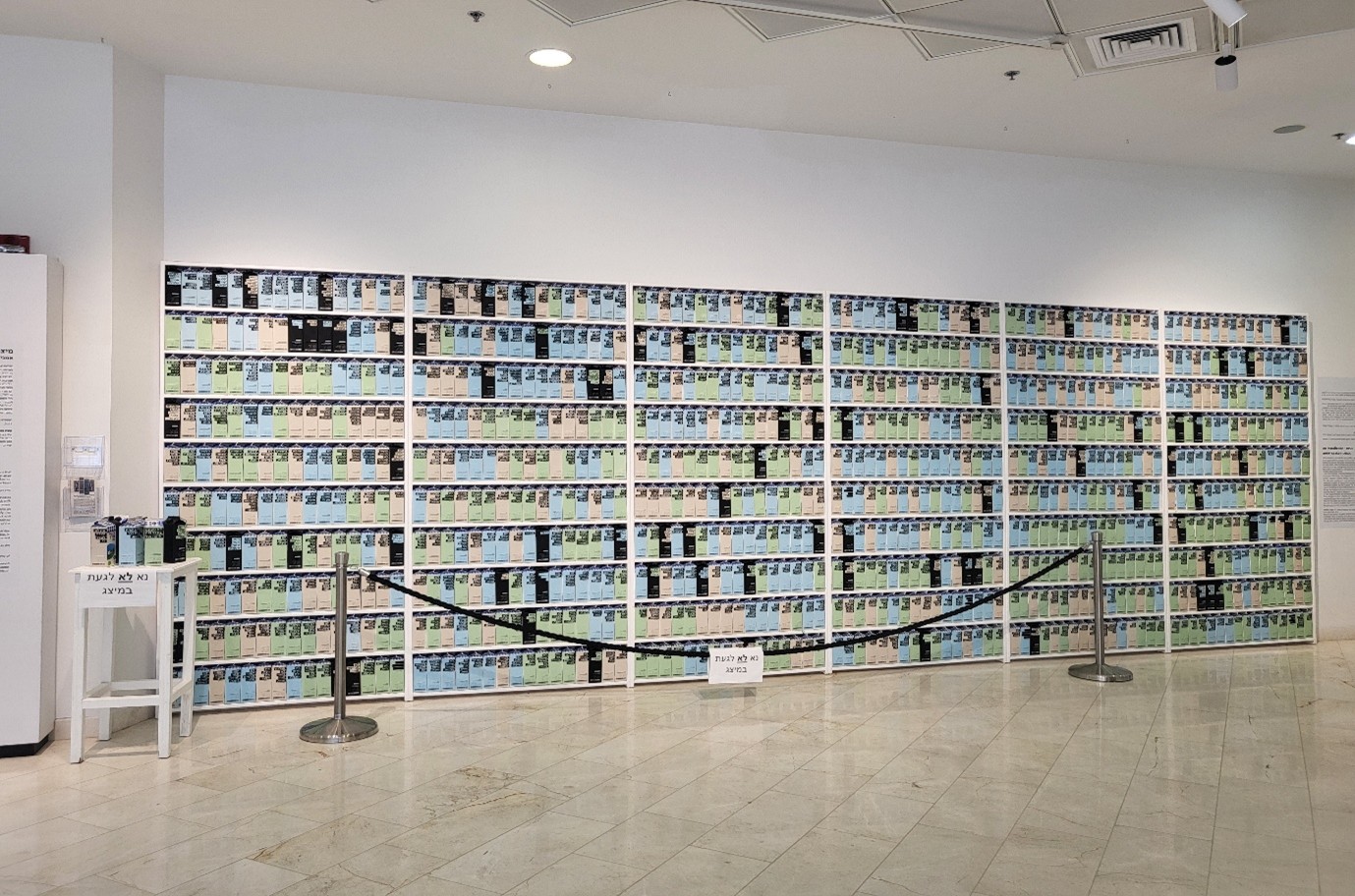

The bitter fate of some Adeni Jewish children in Israel who suffered under what is commonly known as the Yemenite, Mizrahi and Balkan Jewish Children’s Affair has been honoured in an installation piece that can currently be viewed at the Yemenite Jewry Heritage Centre & World Jewish Communities in Rehovot. The piece has been created by Keshet Cohen who is from Dimona in Israel and was submitted to the Bezalel Academy of Art and Design, Jerusalem as a final project by Cohen in 2020/2021. It consists of 1053 replica milk cartons of four colors; green, beige, blue and black. These milk cartons represent those children who vanished when the Israeli state itself was in its infancy, either through adoption without parental consent or premature death. The colors stand for the different investigations various Israeli governments have held into the scandal, though the black cartons are for those children whose fate the various commissions could not resolve. The piece is disturbingly beautiful (given the subject matter) and speaks to the undoubted innocence of the persecuted children in question. It also sobers conventional attitudes about the meaning that is to be given to Adeni (and indeed North Yemeni) Jewish migration to Israel. As the installation’s tombstone reads, one of Aden’s links to Israeli history is in truth a “thick scar”.

The 1053 installation, Rehovot (Credit: Fatimah Johnson)

It is to be noted that some 70 years after modern Israel was established, people still marvel at how so many Jews from both Yemens came to be in Israel. An album put together by the Israeli artist Itamar Siani, whose family hailed from Sanaa, entitled The Magic Carpet can be found currently in the Yemenite Jewry Heritage Centre & World Jewish Communities in Rehovot. The album recollects his journey from Yemen to Aden to Israel in 1949. This journey is described in a grand tombstone using the words of Israel Yeshayahu (speaker of the Knesset in 1973 and a North Yemeni) as an “Aliya” (religious emigration), as “legendary”, as being facilitated by a “Magic Carpet”, as a redemptive “ingathering” of “ancient and loyal” Jews that constituted salvation from “darkness” and persecution. Israel by deliberate contrast is described as “free” and “cultured”. The facts are that by late 1950, 47,000 Jews from Yemen and Aden had permanently migrated willingly to Israel via a harrowing process initiated by: the then Israeli Government with the assistance of US Jewish organizations, plus the agreement of the ruler of North Yemen, Imam Ahmed bin Yahya, the sultans of the protectorate between Aden and Yemen and the British ruling officials in Aden. This multilateral process had begun in December 1948. [10] Hundreds of people died on route to Israel, either on the journey between Yemen and Aden or in Aden itself (429 people are known to have died in the Hashed refugee camp in Aden), up to 250 people died near the borders of Yemen in September to October 1949 and for example significant numbers (3,000) needed urgent hospitalisation on arrival in Israel in 1949 that the state could not accommodate. The majority of the 30,000 people who arrived in Israel between July and November 1949 were suffering from malnutrition and were diseased. [11] The name of the migratory process was given as Operation Magic Carpet by the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (JDC) who ran the operation in practice. The name of the operation has been severely criticized for being racist; the name locks those Jews transported to Israel into a context of their alleged primitiveness – that they saw the airplanes used to airlift them as the magical carpets that feature in a Thousand and One Nights. Further evidence of this racist attitude to Eastern Jews is found in the name of the operation to bring Iraqi Jewry to Israel; Ali Baba. In Meir-Glitzenstein’s article she shows how images were invented and then disseminated about the migration of Jews via Aden that gave them overtly mythical, messianic as well as orientalist meanings in the service of creating: “the dichotomy between the Jews and Israel on the one hand and the Arabs and Arab countries on the other”. [12]

An album of 15 etchings by Siani (Credit: Fatimah Johnson)

While a huge amount of focus has centered on the supposed glamour of mass Jewish departure from Aden in the mid 20th century, departure from Aden to England preceded it in the 19th century. This was alongside other Jewish members of Britain’s Eastern Empire, those from Burma and India. Historian Adam Mendelsohn tells that they were enthusiastically welcomed into English high society partly because of their huge wealth, even enjoying the attention of the Prince of Wales (Albert Edward, later Edward VII). Mendelsohn further informs that ultimately Adeni Jewry in England did little to push for religious reform and modernisation opting instead to assimilate with the established elite of Anglo-Jewry. [13] Roughly, a hundred years later the pattern of migration from Aden to England continued but under significantly humbler circumstances. The majority of Adeni Jews who left Aden for England in the 1960s were middle class and congregated in a section of North London (Stamford Hill) where they have prospered. Oral testimony from a British Adeni (below) shows the strength of the respectful connection they still have to South Yemen in the locality of Aden. This coupled with the intimate knowledge Jewish Adenis in Britain and Israel hold in regard to Aden has the potential to promote understanding and kinship between the three countries:

It is exactly the same with the Adenites – we always feel Aden was the good time of our lives. Whoever remembers Aden or was born in Aden will always say there is not a place on earth like Aden.

:

[1] Dani Goldsmith, 1998, The Menahem Messa Family and the Aden Jewish Community During the Years 1839 – 1937, Tel Aviv University

[2] The Jews of the British Crown Colony of Aden – History, Culture and Ethnic Relations, Reuben Ahroni, E.J. Brill, Leiden, 1994, p1

[3] The Jews of the British Crown Colony of Aden – History, Culture and Ethnic Relations, Reuben Ahroni, E.J. Brill, Leiden, 1994, p2

[4] The Jews of Aden, Ed. Rickie Burman, The London Museum of Jewish Life and Kadimah Youth Movement, London, 1991, p8

[5] Exiles – Edward Said, Dir. Christopher Sykes, British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), 23 June 1988

[6] arabnews.com

[7] Notes on Nationalism, George Orwell, Penguin Random House, UK, 2018, p1

[8] Notes on Nationalism, George Orwell, Penguin Random House, UK, 2018, pp1-2

[9] The Merchant of Venice, William Shakespeare, Harper Collins, London, 2013, Act 4 Scene 1

[10] Operation Magic Carpet: Constructing the Myth of the Magical Immigration of Yemenite Jews to Israel, Israel Studies , Vol. 16, No. 3, Esther Meir-Glitzenstein, Indiana University Press, USA, 2011, p151

[11] Operation Magic Carpet: Constructing the Myth of the Magical Immigration of Yemenite Jews to Israel, Israel Studies , Vol. 16, No. 3, Esther Meir-Glitzenstein, Indiana University Press, USA, 2011, p150

[12] Operation Magic Carpet: Constructing the Myth of the Magical Immigration of Yemenite Jews to Israel, Israel Studies , Vol. 16, No. 3, Esther Meir-Glitzenstein, Indiana University Press, USA, 2011, p169

[13] Colonialism and the Jews – Not the Retiring Kind Jewish Colonials in England in the Mid-Nineteenth Century, Adam Mendelsohn, Indiana University Press, USA, 2017, pp 93-95

[14] The Jews of Aden, Ed. Rickie Burman, The London Museum of Jewish Life and Kadimah Youth Movement, London, 1991, p45

Previous article

Next article